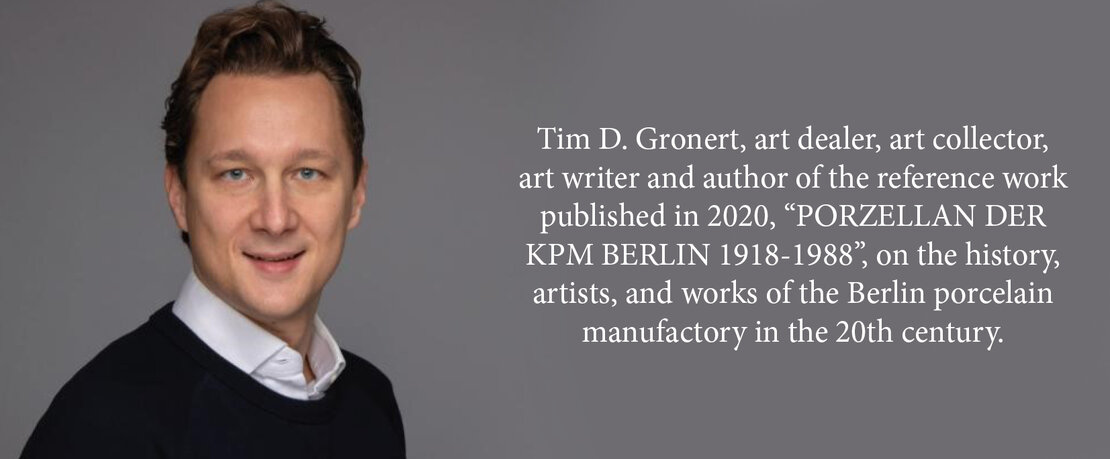

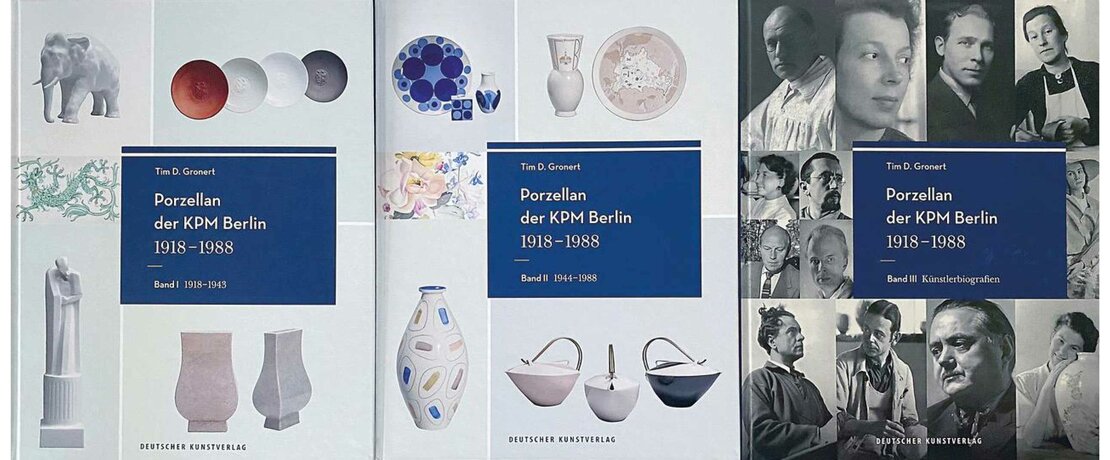

50 years of innovation under the sign of the scepter

Porcelain of KPM Berlin 1918-1968

Only a few months after the end of the First World War, the abdication of the German Emperor and the proclamation of the Republic, the political decision-makers decided to rename the venerable Berlin Porcelain Manufactory, and so Royal became State. To keep with tradition, but also with a view of maintaining a certain continuity in the field of promotional marketing, the old electoral Brandenburg scepter was retained as the company’s signet, as was the abbreviation KP, whilst the name Royal Berlin was used in advertising on the increasingly important U.S. market. With this change of name, a period of around 50 years began during which numerous artistic, technical, and strategic innovations shaped the course of the Berlin State Manufactory, which was to continue to serve as the model company for the entire German porcelain industry.

Initially, the artistic director of the manufactory, Theo Schmuz-Baudiss, encouraged some of his most capable employees – who, like him, had long suffered under the conservative officials who were devoted in matters of art to the retro preferences of the dynasty – to create freer designs in form and decoration. This hitherto suppressed openness was accompanied by a certain reorientation towards contemporary tendencies in the art world which blossomed under the directorship of Nicola Moufang between 1925 and 1928. Under Moufang, the manufactory cooperated closely with the reputable artists amongst the teaching staff at the Berlin Art Academy, the Vereinigten Staatsschulen für freie und angewandte Kunst, reformed under Bruno Paul from 1924. As well as the models and painting designs of the established painters, sculptors and craftsmen who now worked for KPM, emerging young talents were also trained in the jointly run Ceramic Specialist Class. In addition, Moufang used his extensive network to attract freelance artists such as Ruth Schaumann, Richard Seewald or Tommi Parzinger to design for the KPM and to establish its own unique, playfully-elegant form of Berlin Art Deco.

A forward-looking advertising strategy was also initiated in the second half of the 1920s to establish the KPM brand internationally. This consisted of numerous exhibition participations at home and overseas, the complete modernisation of the sales rooms at Leipziger Platz by famous artists, a far-reaching corporate identity devised by the young graphic artist Johannes Boehland, and porcelain gifts from the traditional company treasure trove publicly directed at important figures.

Following Moufang, the subtle Günther von Pechmann shaped the history of the manufactory for almost ten years. His was the important task of bringing KPM into the machine age, i.e. to design and produce modern utility porcelains that represented the spirit of the age in form, without ornamentation, which could easily be reproduced by machine. The new models for the so-called new home should of course be artistic and, in times of international economic crises, not exceed the price constraints. Two particular artist personalities helped the manufactory and its director to successfully carry out this demanding remit: On the one hand, the former Bauhaus student Marguerite Friedlaender - as head of the newly established porcelain workshop in cooperation between KPM and the Staatlich-Städtischen Kunstgewerbeschule Burg Giebichenstein in Halle/Saale - brought her refined, perfectly crafted models to series maturity. On the other, KPM grew in force within the manufactory with the young designer Trudi Petri - who had trained in the Ceramic Specialist Class - who masterfully solved the set tasks with her functional designs. Further innovations were ensured by the researchers at the manufactory’s Chemical-Technical Research Institute, who, in line with the demands of the time, devised new types of decoration, for the decorative porcelain painting favoured by Moufang was in part no longer fashionable, and, in any case, was difficult to finance.

Technical and laboratory porcelains, which had always accounted for a large part of sales, were thus transformed into undecorated utilitarian objects and/or service pieces. Then again, the chemists now developed entirely new forms of surface decoration for the modern services, dishes, vases and boxes, which could now be offered either completely in white or celadon, craquelé, basalt or lustre decoration.

Thus, even into the 1940s, the Staatlichen Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin was still producing art and utility porcelains that can be described as contemporary modern in relation to the former prevalent International Style and the influence of the Bauhaus on arts and crafts production at the time. Production also received new impetus in the fields of painting and relief decoration through skilled personalities such as Else Möckel and Gerhard Gollwitzer.

Although Director Pechmann and his often progressive colleagues were repeatedly harassed by the National Socialist rulers from 1933 onwards, the great successes at home and abroad saved the manufactory for some time from political influence. In 1938, Pechmann was removed however from his office, but the Prussian Finance Minister responsible for KPM, Johannes Popitz, was able to appoint the proven porcelain expert and former Meissen director Adolf Pfeiffer as his successor instead of a party bigwig. Under his leadership, porcelain sculpture experienced a new, albeit brief upturn even during the war, culminating in the decoration of the Berlin State Opera on the Unter den Linden boulevard and the centrepiece ‘Geburt der Schönheit’ (Birth of Beauty) designed by Paul Scheurich.

The extensive destruction of the manufactory grounds and the production facilities in Berlin’s Tiergarten by Allied bombing in November 1943 marked the end of an important chapter in KPM’s history, but opened up a new one with the rapid execution of the already planned evacuation of the remaining workforce and all remaining means of production to an alternative factory on the Upper Franconian porcelain town of Selb. Here, KPM consolidated itself soon after the end of the war under the new director Werner Franke, initially by rebuilding the technical department; after only a short time, however, new forms for art and utility porcelain were created again. The swift economic development of West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s led to the steadily growing demand for modern porcelain with contemporary decoration. Trude Petri – living and working in Chicago from 1959 – and Siegmund Schütz continued to be primarily responsible for the models, as well as Friedlaender’s former student Hubert Griemert after 1952. The two artists Sigrid von Unruh and Luise-Charlotte Koch, who had been permanently employed as artistic designers since 1946, were particularly operative in the appropriate decorations for the new pieces, and their ingenuity and technical skills decisively shaped the overall image of the manufactory for more than 20 years.

Production resumed in the lavishly modernised workshops in Berlin from 1955, whereby the displays in the manufactory sales outlets were also always seen as (show) windows to the free world after partition and the building of the Wall. The appointment of Stephan Hirzel as production auditor and artistic advisor for new developments on the occasion of KPM’s 200-year anniversary in 1963 brought a new artistic impulse. Through the commission of external, established, as well as up-and-coming artists, he achieved remarkable successes until 1970 in modernizing the porcelain offer, before a decade of mismanagement and political corruption caused a steady decline in the artistic development of the now state-owned company.

In 1988, the manufactory officially regained the name Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin, and further long years passed before KPM, privately owned by Jörg Woltmann since 2006, was able to produce aesthetically innovative and artistically appealing porcelains. It is hoped that instead of reverting to older models and paintings from the company’s history, the development towards contemporary forms and decorations will be consistently pursued in the future. History has shown that external impulses have always had a stimulating effect on the product range of Berlin’s oldest manufactory still in production. Long may the blue scepter stand as a symbol for innovation and modernity in porcelain production in the 21st century, and may the objects created under it fill us with joy and wonder. The spindle shaped Kruke vase named after the classic storage vessel for medicinal ointments or pastes was one of the first models designed by Trude Petri in her adopted home of Chicago which from November 1951 was produced in the outsourced plant in Serb, and from November 1955 in the extensively renovated main facility of the Berlin manufactory. The simple form and balanced volume exemplify Petri’s aspiration for clear, timeless lines. In the 1950s, the vase was given various painting decorations by the two leading KPM designers Luise-Charlotte Koch and Sigrid von Unruh. Shown here are two very rare and interesting period-typical examples in the characteristic KPM colours of the time, both vertically structured, one with monochrome ground stripes and one with planes and patterns generated by oscillations. In both cases, form and decoration are in perfectly harmonious alliance.