Frederick II: Decorator of an epoch (1740 - 1790)

On occasion of the Prussian Sale we have divided the timespan between 1701 and 1918 into chapters, introducing their most influential players, commentators, and styles. Take a look and let us surprise you!

Frederick II: Decorator of an epoch

The apple never falls far from the tree? In the case of Frederick II and his father Frederick William I, this paternal ideal could not have been further from the truth. Whilst Frederick William, known as the Soldier King, did everything in his power to put an end to the extravagance of his forebear by fostering a Spartan atmosphere within his court and state, his son Frederick II happened to be born during one of the most whimsical and opulent artistic eras Europe has ever seen: The Rococo. However, in his case it was not considered a period of decadence, as Marie Antoinette’s France would be. Frederick II’s thoughts on the duty of kings are recorded in a political treatise of 1752: “The ruler is not raised to his exalted rank and entrusted with the highest power for him to grow soft, living blissfully from the fruits of his peoples’ labour whilst everything around him corrupts. The ruler should be the principal servant of the state.” In the age of Absolute Monarchy, this subversion of values can be considered a significant step towards modernity.

“The ruler should be the principal servant of the state.”

How can the Rococo style be reconciled with Frederick II’s principles? The Rococo can be viewed as an aesthetic rebellion against the geometric order that forms the foundation of a military state. From the camp bed to the parade: Army life is dictated by the stark regularity of horizontal and vertical lines, designed for clarity, efficiency, and pragmatism. The Rococo style is governed by the exact opposite. The straight lines that previously ordered space are forced to give way give way to innumerable scintillating curves. Surfaces come alive and move as erratically as a veil in the wind. The Rococo rejects symmetry. Gables, mouldings, corners, and edges no longer serve to bring order or closure to a space, but are instead denoted to a framework for dynamic arabesques and floral garlands. From walls and facades to plates and silver spoons, everything becomes a stage from which to stimulate and enrapture the soul. Like a canvas, architecture and objects become the mere foundation of a new work of art.

Thanks to his patronage, the playful and elegant Rococo style flourished. The King even contributed to its development: Frederick II’s beloved palace Sanssouci was constructed after his own design, which he discussed and planned together with the architect Georg von Knobelsdorff, from whom two fine paintings in this catalogue originate (lot 19). Although the “Frederician Rococo” assimilated French and Dutch influences, it was at pains to ameliorate the excessive tendencies of the style, treading an idiosyncratic path between Baroque, Rococo, and Classicism. Thus, the Frederician era developed its own aesthetic signature with unique ideals of beauty and managed to emancipate itself from the leading influence of the French court.

As a young man, Frederick II was forbidden from musical pursuits, although he showed considerable talent for music, writing, and drawing. His father did not think highly of such effeminate activities, as he saw no military usage for them. Ironically it would be Frederick who would later make excellent use his father’s army. Despite his passion for the military, Frederick William only led his forces into war on one occasion: The Pomeranian campaign of 1715. The court goldsmith Lieberkühn was one of the few cultural bridges between father and son. He was the author of the pair of candlesticks with royal monograms presented in this catalogue (lot 29).

“Anyone can acquire knowledge, but the art of thinking is the rarest gift that nature can bestow.”

The end of the second Silesian War earned Frederick the moniker “the Great”. Although this characteristic remai-ned, in the course of his life his people came to known him as “Old Fritz”. The exhaustion of the later Seven Years’ War frequently brought the King to the brink of his existence, but it also rewarded him with a priceless treasure: Porcelain. Although the Berlin manufactories of Wegely and Gotzkowsky had experienced some success in 1751, as illustrated by the Wegely porcelain vase (lot 39), it was the knowledge gained through Frederick’s victory over Saxony which finally allowed him to found his own royal porcelain manufactory – KPM – in 1763. The Royal Berlin Porcelain manufactory still uses the sceptre of the Electoral coat-ofarms of Brandenburg as its trademark to this day. Frederick II contributed greatly to the success of “his” manufactory with numerous extensive orders, many of which you will find among the examples in the following chapter, such as the service for Berlin City Palace in lots 88–97. Frederick was infected by the “Maladie de porcelain”, having already ordered numerous services from Meissen throughout the Seven Years’ War, designed according to detailed instructions. One such piece is the cloche from a service later known as the “Möllendorf Service” (lot 50).

“In my state, every man can seek happiness on his own terms.”

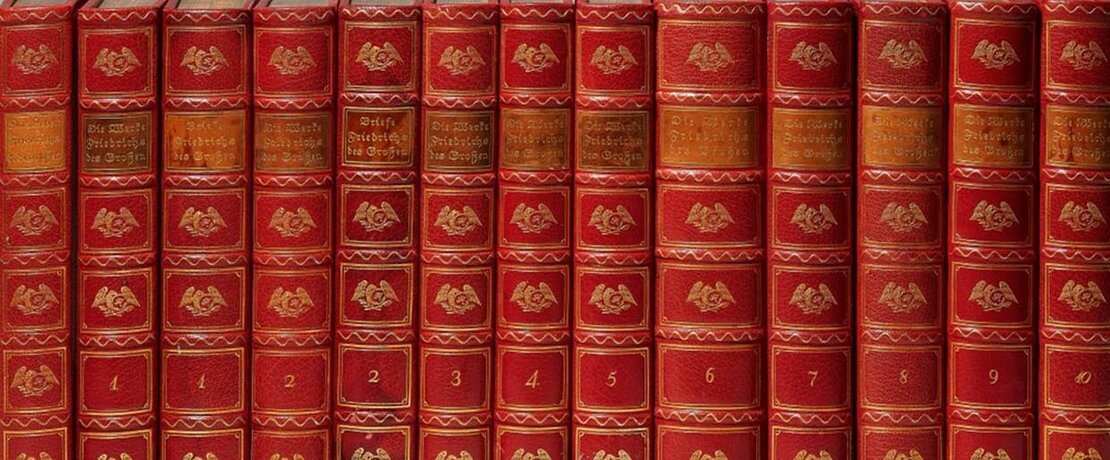

Blessed with a sharp mind, Frederick II was active as an author, historian, and composer. He was famed for his universal learning, a quality for which even his enemies admired him. As a child of the Enlightenment, Frederick placed great import upon the potential of individual thought. Tolerance was one of the principal values upon which he aimed to build his state, knowing it to be one of the greatest motivators for action. He emphasised, “In my state, every man can seek happiness on his own terms”. He became an unparalleled patron of philosophy and the arts. Although a highly cultured man himself, he knew that this was not enough: “Anyone can acquire knowledge, but the art of thinking is the rarest gift that nature can bestow.” The fine portrait of the King by Charles-Amédée van Loo (lot 13) is already mentioned by Fontane, and is certainly worth a second or third look. Those wishing to get to know the King better can also refer to his extensive written opus. In this catalogue you will not only find two original letters written by the King of Prussia (lots 28 and 51) but also a complete edition of his collected works bound in Maroquin (lot 127).

Vivat Fridericus Magnus

The year 1745 did not begin well for Prussia. Frederick II was in the midst of a war against Maria Theresa, Queen of Austria and Silesia. On 8th January 1745, Maria Theresia increased her military strength even further by forming a quadruple alliance against Prussia comprising Austria, the Netherlands, Britain, and Saxony. Despite these seemingly unbeatable odds, the Prussians were able to beat the armies of the alliance at Hohenfriedberg, Soor, and Kesselsdorf. This resulted in the Peace of Dresden, signed on 25th December 1745, in which Maria Theresa relinquished Silesia and it became a part of Prussia. Upon his return to Berlin, Frederick was for the first time commended as “the Great”. The citizens of Berlin were so enthused that banners of “Vivat Fridericus Magnus” decorated many houses. The peace not only benefitted national morale, but also brought considerable economic perks: Saxony was forced to pay one million Taler in reparations to Prussia. The newly gained territory of Silesia was also rich in mineral resources, including silver, which was an important source of Prussian wealth.

„The man who appeals to the imagination will always triumph over he who appeals to reason.“

These two candlesticks, designed by Christian Lieberkühn the Younger in 1746/47 as part of a new silver service for Frederick II, can be related directly to his military fortune in the Second Silesian War. Lieberkühn was among the most accomplished goldsmiths of the mid-18th century. As court goldsmith to Frederick II during the war, he was decisive in the creation of a style that was to develop further during peacetime.

Candlesticks made in 1746/47 still follow the formal canon of the Baroque, whereas those for Sanssouci palace, built in 1747, already incorporate Rococo elements. Frederick II was heavily involved in the planning of the palace, as well as the design of much of its porcelain and silver. Therefore it is possible that these candlesticks not only bear the Prussian King’s monogram, but may have been designed and used by him also. Silver from the Frederician era is rare on the art market. Frederick William III ordered many works by Berlin goldsmiths to be smelted down in 1808 to afford the first million in reparations demanded by Napoleon, and thus very few of these valuable pieces have survived to this day.