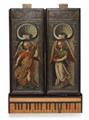

A small portable organ, a so-called “bible regal” from Berlaymont Convent in Brussels

Oil paint on softwood, resonators, pipes and brass registers. The keyboard made from boxwood veneer on oak. The two folding bellows made from parchment, each with six pleats. An organ designed to be placed on a table constructed from three parts: An oblong corpus comprised of the two bellows placed on top of one another with a hollow section on the inside to hold the keyboard. The moulded edges of the corpus of ebonised wood, the upper faces of the bellows each decorated with a full-figure depiction of an angel making music within a rounded arch with shell motifs en grisaille. The edge of the keyboard painted on three sides, the upper section with a band of foliage, the sides with winged angel's heads. Dimensions when extended H 12.5, W 61.5, D 91 cm.

Attributed to Nuremberg, last quarter 16th century.

If one had asked a contemporary of King François I (1494 – 1557) or Henri IV (1553 – 1610) of France what a regal is, they would have been surprised by the question. The instrument was so common at the time that no one would have needed to ask. The regal has all but disappeared today, although some surviving examples can be found in the collections of larger museums. The regal is a small portable organ with beating reeds, comprised of two bellows and a keyboard. In this regal, the bellows form a case to transport the keyboard when stacked on top of each other. The fact that the instrument is more or less the size of a Bible, the similarity of its ornate decoration to a manuscript, and the way in which the tops of the bellows resemble book covers led to it acquiring the name “Bible regal”.

This remarkable and particularly beautiful example once belonged to Countess Marguerite de Lalaing of Berlaymont (1574 – 1651). She founded Berlaymont cloister, a women's convent of Augustinian canons, together with her husband Florent de Berlaymont in 1625. According to tradition, the organ was a gift from the regent of the Spanish Netherlands, Archduke Albert VII of Austria (1559 - 1621) and his wife Infanta Isabella-Claire-Eugenie of Austria (1566-1633), daughter of Philipp II of Spain.

The instrument appears in literature for the first time in a book by Edouard C.G. Gregoire, where it is erroneously dated to the 15th century. Several years later, in 1876, we are provided with a detailed, though still erroneous, description of the organ by François-Joseph Fétis: « J'ai sous les yeux un petit orgue régal qui paraît avoir été construit au quinzième siècle, et peut-être au quatorzième, car les peintures dont il est orné sont exécutées au blanc d'œuf. La largeur de la boîte qui contient le clavier, les tuyaux en cuivre et le mécanisme des soupapes n'est que de huit pouces environ, et sa hauteur, de cinq. Deux soufflets, dont les cavités lui servent d'enveloppe lorsqu'on veut transporter l'instrument, s'adaptent à des petits porte-vent saillants. Les tuyaux, dont le plus long n'a pas plus de quatre pouces et demi et huit lignes de diamètre, sont placés dans une position horizontale. Ce ne sont pas ces tuyaux qui chantent lorsque l'instrument est joué, mais les anches en cuivre qu'ils contiennent. Ces anches battent sur les parois de leur bec, ce qui donne à leur son une intensité dure et rauque qui surpasse celle de certains orgues volumineux composés d'une réunion de plusieurs jeux. Ce curieux instrument appartient au Couvent de Berlaimont à Bruxelles; on le garde comme une précieuse relique, parce que la fondatrice du couvent (morte au seizième siècle) en jouait ». (I have before me a small organ that appears to have been built in the 15th century, perhaps in the 14th, as the paintings upon it have been done in egg tempera. The width of the case, that contains the keyboard, the copper pipes and the vent mechanism, measures just eight inches, the height five. The two bellows, the hollows of which serve as a case for the instrument when it is transported, are attached to two small flaring wind chests. The pipes, the longest of which measures not more than four and a half inches and eight lines diameter, are placed in a horizontal position. It is not the reeds that make a sound when the instrument is played, but the brass reeds that they contain. The reeds beat against the walls of their resonators, which lends their sound a harsh, raw intensity, that even exceeds that of some larger organs that consist of a combination of several registers. This curious instrument belongs to the Berlaimont cloister in Brussels, where it is kept like a precious relic, because the founder of the cloister (who died in the 16th century) played it”.)

In his expertise, Patrick Collon lists 38 further similar published and identifiable small organs in numerous international museums and private collections, including nine Bible regals like the present work. Due to its similarity to a piece in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum made by Michael Klotz, Collon attributes it to Nuremberg. There were many well known instrument makers in Nuremberg, including several organ makers in the 16th century. They were carefully monitored by Nuremberg city council and they were only allowed to take on one apprentice in order to ensure that they did not compete with the town's carpenters. Today, only a handful of Nuremberg organs have survived, the majority of them brought into connection with the names Stephan Cuntz (1565 - 1629) and Nicolaus Manderscheidt (1580 – 1662). In contrast to church organs, regals went out of fashion in the 18th century, as their sound no longer met the requirements of modern listeners.

Certificate

With an expertise by Patrick Collon, organ maker from Brussels.

Provenance

From the de Berlaymont Convent, Brussels.

Literature

Described in Gregoir, Histoire de l’orgue suivie de la biographie des facteurs d’orgues et organistes Néerlandais et Belges, Brussels-Antwerp 1865. Described in Fétis, Historie de la Musique, Paris 1869 – 72. Cf. also Leipp, La Régale, in: Bulletin du GAM, Faculté des Sciences no. 38, Paris 1968. Cf. also Mountney, The Regal, in: Galpin Society Journal XXII, London 1969. Cf. also Menger, Das Regal, Tutzing 1973. Cf. also Schindler, Der Nürnberger Orgelbau des 17. Jahrhunderts, Michaelstein 1991. Cf. also Schindler/Ulrich (ed.), Die Nürnberger Stadtorgelbauer und ihre Instrumente. Orgelbaumuseum Schloss Hanstein Ostheim, Nuremberg 1995.

Exhibitions

In the Church of Saint Michael in Ghent in 2003.