Hermann Max Pechstein

Self-portrait, reclining (Selbstbildnis, liegend)

1909

Oil on canvas. 73.5 x 98.5 cm. Framed. Monogrammed 'HMP' (joined) in brown upper left. - In fine condition with fresh colours. Some faint craquelure.

This work is being offered for sale on the basis of a settlement reached between its consignor and the heirs of Dr Walter Blank through the mediation of Kunsthaus Lempertz. Their settlement has led to the amicable resolution of all open questions regarding the work’s provenance and legal ownership: as a result, its buyer will be purchasing this property unconditionally, free from claims of any sort.

With “Self-portrait, reclining”, Hermann Max Pechstein’s most important self-portrait is being offered for sale. It is from a period generally considered to be the best phase of his oeuvre – a highlight of German Expressionism.

A request has been made for the painting to be loaned to the exhibition “Max Pechstein – Die Sonne in Schwarzweiß”, to be shown at the Museum Wiesbaden, 15 March–30 June 2024, in cooperation with the Kunstsammlungen Zwickau – Max Pechstein-Museum, the Brücke Museum Berlin and the Max Pechstein Urheberrechtsgemeinschaft, Hamburg/Berlin.

“Sef-portrait, reclining” (1909), Max Pechstein’s earliest painted self-portrait, is energetically painted in luminous colours. Previously the artist had only depicted himself in two small woodcuts of a private character. Here, by contrast, he has self-confidently presented himself as a full-length figure filling the entire image in a wholly unconventional manner. Reclining on a green surface, he leans on one elbow as he extends the other arm, which holds the brush he is using to paint the canvas that reaches just into the image.

This extraordinary, museum-quality self-portrait captivates us with its complementary contrasts of red–green and blue–yellow, which Pechstein has selected in order to establish the greatest possible luminosity and sense of presence. Its bold colours coincide with the painter’s direct and almost defiant gaze. Pechstein, who found himself on the threshold of his artistic breakthrough in 1909, looks to his future with self-assurance.

The breakthrough

For this artist, 1909 was a period defined by seminal changes. He was 28 when he created this work; he had been living in Berlin since mid-1908 and had initially still been largely penniless. Thus the spring exhibition of the Berlin Secession marked a milestone in what was still the early career of the artist: he was represented by three paintings there and was able to sell two of them. Looking back, he would write: “The ice was broken, and my art, which art scholars later called ‘Expressionism’, had successfully begun to take its course” (cited in Aya Soika, Max Pechstein. Das Werkverzeichnis der Ölgemälde, vol. 1, Munich 2011, p. 13).

First stay in Nida

The proceeds from these purchases are what first enabled Pechstein to spend his summer by the Baltic Sea, in the fishing village of Nida on the Curonian Spit, where he worked from the end of June to the beginning of September, in the open countryside and far from the big city. It was the first of many summers spent in this “painter’s paradise”, as Pechstein called it. He was fascinated by the maritime landscape and the simple life of the locals, with whom he maintained close contact.

“Self-portrait, reclining” was very probably created in late summer, directly following this artistically extremely important stay; in terms of its motif it is still entirely permeated by the impressions he gathered there. This is readily seen in the painter’s suntanned features as well as the manner of dress he adopted from Nida’s fishermen: his simple seaman’s shirt, gaiters and bare feet. The prominent sideburns, which the artist only kept for a brief period, also derive from this context: they are additionally to be found in his lithograph “Zwei Köpfe”, which is from the same period (Krüger L 57, see comp. ill.).

Stylistic new beginnings

Pechstein’s summer in Nida also signalled a stylistic landmark for him. While, at the beginning of 1909, he had still been experimenting with pointillist painting techniques as well as an impasto in the style of van Gogh, he now began working for the first time with large areas painted in homogenous and luminous colours. “Self-portrait, reclining” is one of the earliest examples of this. This artistic achievement was possibly still connected with the Matisse exhibition organised at the Paul Cassirer gallery in Berlin, which Pechstein visited together with Kirchner and Schmidt-Rottluff in January 1909. The nudes and pictures of dancers shown there made a lasting impression on Pechstein – even more so than on the other “Brücke” artists.

Self-portrayal

In the spring of 1909 Pechstein designed the official poster for Emil Richter’s “Brücke” exhibition in Dresden. In it, he presents likenesses of the four members of the “Brücke”, with himself at the bottom left (Krüger H 85, see comp. ill.). Perhaps this first group portrait conceived for public display kindled a desire in the painter to create a deliberate, individual representation of himself. The striking result of this intention stands here before our eyes.

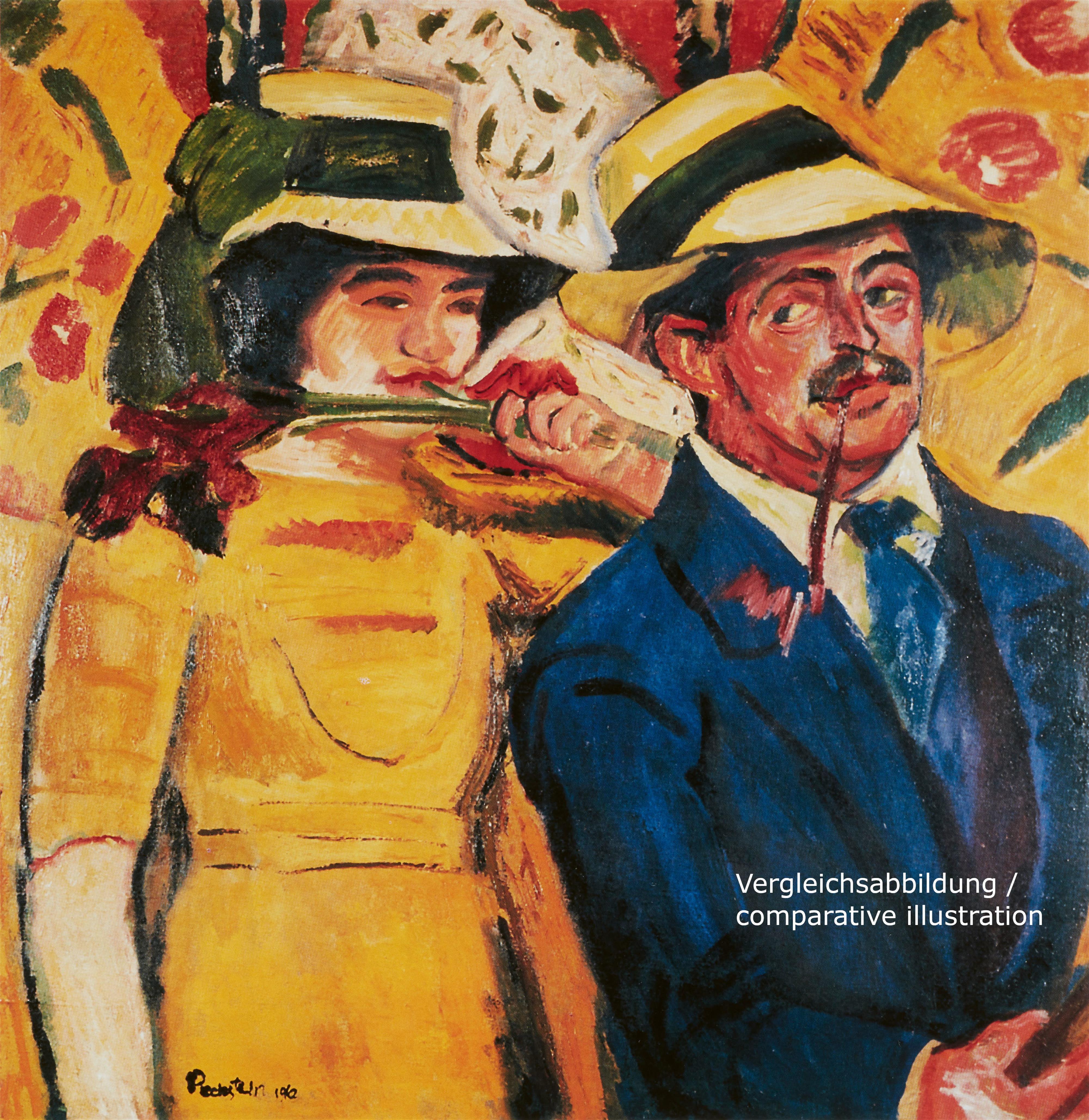

A few months after creating “Self-portrait, reclining”, the painter presented himself with comparable self-assurance in his “Doppelbildnis” (Soika 1910/67, Nationalgalerie Berlin, see comp. ill.), which depicts him together with “Lotte” – his lover and future wife Charlotte Kaprolat. Pechstein was elected president of the “Neue Secession” in May 1910 and served as the eloquent ambassador of the progressive “Brücke” artists. In both self-portraits Pechstein has made it unmistakably clear that he saw himself in a leading role as an artist and as spokesman of the “Brücke”.

How art is created – the self-portrait as programmatic painting

“Self-portrait, reclining” is not just to be seen as an individual self-portrayal of the artist; instead, it possesses an extraordinarily sophisticated and complex visual message.

In his discussion of this painting, Roman Zieglgänsberger makes it clear that the artist was by no means solely concerned with portraying himself in his role as painter. “Instead, it shows how art is created. To be completely precise, it even shows where art is created. […] what is decisive for the painting’s thematic message is that the palette is found at the edge, all the way to the left, and the depicted portion of the canvas is opposite it, at the furthest possible point to the right. This is where the ‘Self-portrait, reclining’ that we ultimately have before our eyes is being created. Another subtle touch is that the painting has (as is only logical) been done in exactly the same colours which are to be found on his palette. This means that Pechstein, in transferring the colours from the palette on the left to the canvas on the right, is executing an ‘artful’ balancing act before our eyes. The primary colours red–yellow–blue as well as the secondary colour green on the palette have to be ‘translated’ into the art on the canvas by the artist who only visibly stands (or, in our case, ‘lies’) at the centre of the work in the self-portrait. Reading the picture from left to right, in the direction of Western writing, we see – through Pechstein – how art is created, specifically: the colours are used to precisely capture the motif and to realise it on the canvas through the tremendous efforts of the artist, who is not just the creator but simultaneously the subject of the image here.

Once we have visualised the complex structure of ‘Self-portrait, reclining’, it becomes clear that Pechstein understood this ‘process of becoming art’ – carried out and exemplified here in an experimental apparatus utilising his own person – not just as a maxim for this one self-portrait but as applying to his entire future oeuvre as well. For Pechstein the body of the painter was accordingly the medium, the resonance chamber, through which the outwardly perceived subject matter first had to pass in order to become art. He is thus saying that the world has to be perceived with all our senses in order to ultimately – intermixed with the individual personality of the artist – be capable of becoming emotional art. Art is not just mind, art is not just the act of painting – art is plainly a matter of the ‘whole body’. A painting could not be more programmatic” (from: Roman Zieglgänsberger, Wie Kunst entsteht. Eine kurze Anmerkung zu Max Pechsteins Programmbild “Selbstbildnis, liegend”; complete text at www.lempertz.com/en/academy.html).

“Self-portrait, reclining” is singular in its unconventional pictorial invention. It is an extraordinary visualisation of the painter’s self-assurance and creative power at the moment of his artistic breakthrough. Like no other painting from that year, it presents Pechstein’s fully developed, unmistakable “Brücke” style for the first time and programmatically stands for his understanding of art.

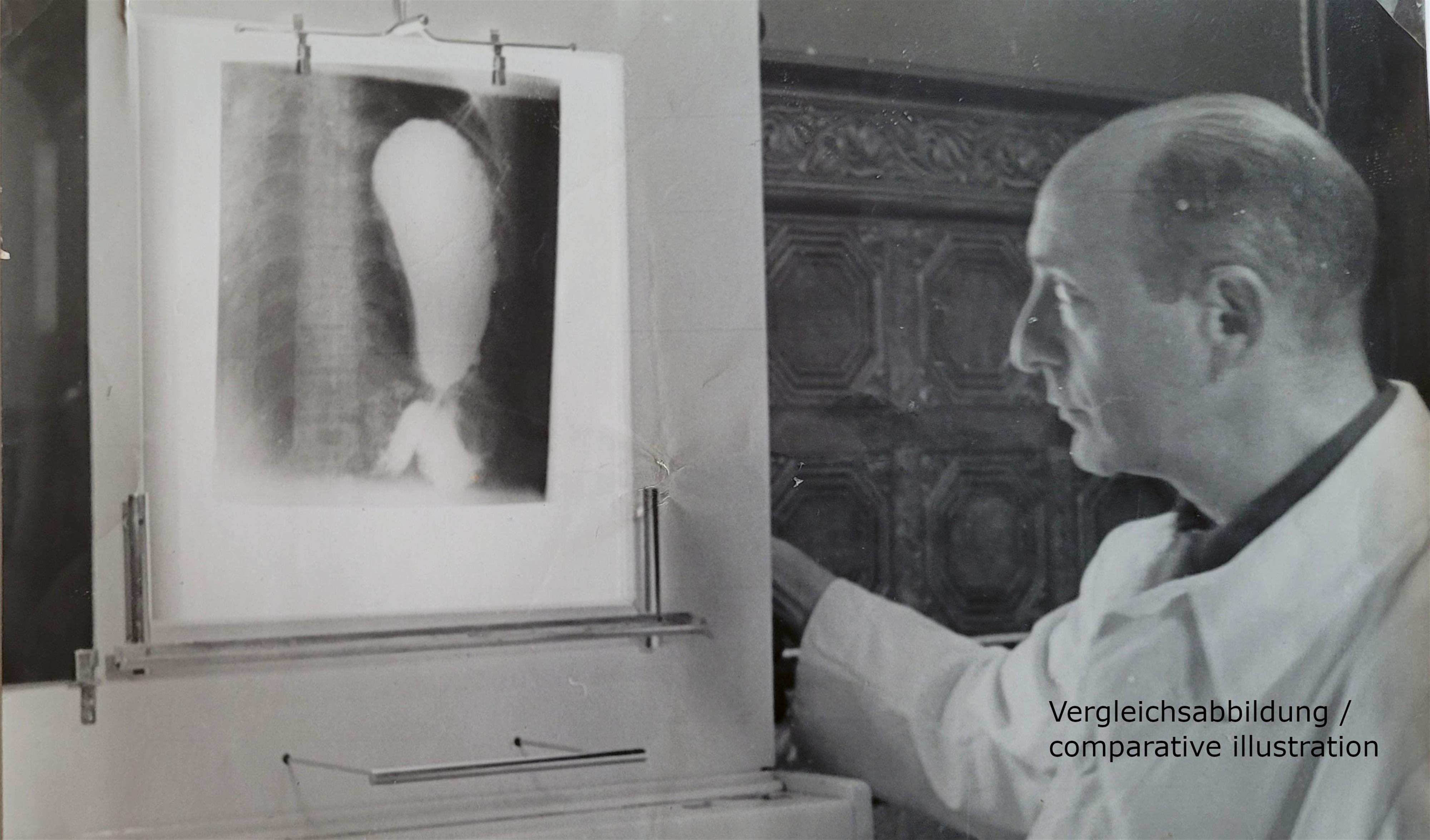

The collector Dr Walter Blank

Dr Walter Blank (1892-1938) came from a Jewish family from the Hörde district of Dortmund. After completing medical school in Bonn, he was deployed on the western front as a major in the medical corps. From 1920 he lived with his wife Martha and their two sons in Cologne: he had a practice for internal medicine, and from 1927 he headed the radiology department at the Jewish hospital. Returning from the war as a staunch pacifist, he was one of the founders of the “German League for Human Rights” and a member of the Socialist Party.

From 1920 the Blanks began building up their significant art collection, which was focused on expressionism and the “Cologne Progressives” group and also contained works by Otto Dix, Marc Chagall, Heinrich Hoerle and Franz Wilhelm Seiwert in addition to Max Pechstein’s self-portrait.

After the Nazis seized power in 1933, the Blank family was subjected to harassment. Martha Blank died in 1935 following a severe illness and Walter Blank and his two sons emigrated to Antwerp in 1936. From there, he moved to Spain to fight in the civil war on the side of the international brigades. Walter Blank died in 1938 in Mataró, near Barcelona.

Catalogue Raisonné

Soika 1909/55

Provenance

Collection Dr. med. Walter Blank, Cologne; Collection V.A., Rhineland; since then in family ownership, in third generation

Literature

Robert Breuer, Max Pechstein - Berlin, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, vol. 29, October 1911 - March 1912, issue 6, pp. 423-431, with illus. p. 429; Walther Heymann, Max Pechstein, Munich 1916, with illus. p. 7; Max Osborn, Max Pechstein, Berlin 1922, p. 168; Jean Leymarie/Ewald Rathke, L'espressionismo e il fauvismo. Parte seconda, volumi 8 (L'Arte Moderna), Milan 1967, colour illus. p. 129; Diether Schmidt, Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein! Selbstbildnisse deutscher Künstler des 20. Jahrhunderts, Berlin (Ost) 1968, p. 270, colour illus. plate 9; Ewald Rathke, L'Espressionismo, Milan 1970, p. 55 with illus.; Jubiläumskalender Firma Heidenhain/Traunreut, 1972, illus. August; Braunschweiger Zeitung, 20.3.1982, Ausstellungsbesprechung, with illus. Andreas Andermatten, Max Pechstein, in: Pan, 1985, issue 6, pp. 4-21, with colour illus. on the cover; Ewald Rathke, Expressionismus von Paul Gauguin bis Oskar Kokoschka, Herrsching 1988, with colour illus. 29; Andreas Hüneke, Zweierlei Augen - Ein Deutungsvorschlag, in: Magdalena Moeller (ed.), Schmidt-Rottluff. Druckgraphik, Munich 2001, with illus. p. 44; Roman Zieglgänsberger, "Es war immer dieselbe Pfeife". Max Pechstein in seinen Selbstbildnissen, in: Max Pechstein. Künstler der Moderne, exhib. cat. Bucerius Kunst Forum, Hamburg 2017, pp. 167-170.

Exhibitions

Königsberg 1914; Berlin 1959 (Hochschule für bildende Künste in association with the Nationalgalerie der Ehemals Staatlichen Museen), Der junge Pechstein. Paintings, Watercolours and Drawings, cat. no. 57 with colour illus.; Bonn 1965 (Rheinisches Landesmuseum), Expressionismus aus rheinischem Privatbesitz, cat. no. 36, with full page colour illus. p. 41; Frankfurt am Main/Hamburg 1966 (Frankfurter Kunstverein/Kunstverein in Hamburg), Vom Impressionismus zum Bauhaus. Meisterwerke aus deutschem Privatbesitz, cat. no. 65, with illus.; Paris/Munich 1966 (Musée National d'Art Moderne/Haus der Kunst), Le Fauvisme francais et les débuts de l'Expressionisme allemand/Der französische Fauvismus und der deutsche Frühexpressionismus, cat. no. 258, with illus. p. 342 (two exhibition labels on the stretcher); Düsseldorf 1967 (Kunsthalle), Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts aus rheinisch-westfälischem Privatbesitz. Painting, Sculpture, Hand Drawing, cat. no. 278 with illus. 32; Schaffhausen/Bonn 1972 (Museum zu Allerheiligen/Rheinisches Landesmuseum), Die Künstler der "Brücke", cat. no. 153, with colour illus. plate 17; Braunschweig/Kaiserslautern 1982 (Kunstverein/Pfalzgalerie), Max Pechstein, colour illus. p. 51; Berlin/Tübingen/Kiel 1996/97 (Brücke-Museum/Kunsthalle Tübingen/Kunsthalle zu Kiel), Max Pechstein. Sein malerisches Werk, cat. no. 35 with colour illus.