“The British are fed up with being patronized by the EU”

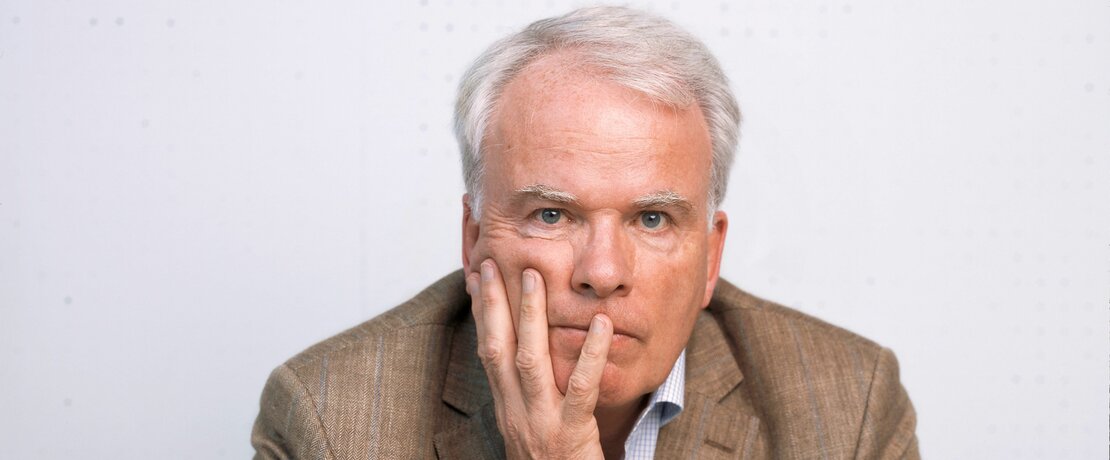

In an extensive interview with daily newspaper Die Welt, Henrik Hanstein discusses the impact of Brexit on the international art market.

By Marcus Woeller

Everyone is expecting a collapse of the British economy after Brexit. Is that at all true? Henrik Hanstein, President of the European Auctioneers, sees the EU rather as the loser.

In three weeks, Great Britain will be an island again. Brexit without a deal threatens. We wanted to know from Henrik Hanstein what effects this would have on the art trade. Hanstein is head of the oldest German auction house, Lempertz, in Cologne, Berlin and Brussels, and President of the European Auctioneers Association.

WELT: Boris Johnson wants to leave the European Union by 1 November. What do your British colleagues in the art trade think about Brexit?

Henrik Hanstein: The City of London is of course a friend of Europe. The EU is a functioning, successful free trade zone. It is advantageous for all sides. There is a run on Paris and Brussels. And according to everything that one hears, the European Commission also assumes that Brexit is coming.

WELT: What do you expect from politics?

Hanstein: Business with Great Britain is becoming more bureaucratic and more difficult, in both directions. Our problem with Brexit is that the European continent is “isolated” from the main trading centre. And as a businessman you moreover have to assume the worst. If there are no transitional periods, things will collapse. First of all, a currency risk threatens. Every continental European who now sends an artwork to London for auction runs the risk that after Brexit the British pound will flounder. Then the seller my get less after the auction than he had expected and agreed.

WELT: And if it isn’t sold?

Hanstein: Then theoretically after 1 November the consignor must pay import sales tax when he wants to get the work back. In Germany that is seven percent for paintings and sculptures and nineteen percent for decorative arts and photography. After Brexit, this would ultimately increase the premium for buyers who want to acquire something at auction and import it into the EU. This tax is prohibitive.

WELT: Christie’s Head of Europe Dirk Boll expressed it more favourably in the “Zeit”, that the EU would probably remain a seller’s market.

Hanstein: Of course, more comes out of Europe to London than the other way around. That is only one side of the coin though, as the traffic routes are considerably obstructed. Great Britain only levies a uniform import sales tax of five percent which is why many large galleries had until now a branch in London to sell through. In recent years, however, the world has become more mobile and quicker, and also much more flexible as a result of digitalization, that I would not be surprised if the weight didn’t shift somewhat after Brexit.

WELT: In which direction?

Hanstein: Paris would surely profit. A few years ago, France reduced VAT from 6.5 to 5.5 percent in order to compete against Great Britain. Brussels also has great advantages in terms of location. It is centrally located for Great Britain, Germany and for half of Europe. Belgium has a uniform import sales tax of only six percent. If for example they wish to bring an important antique collection from the USA to Europe, it is clear where they are importing it to. Not in Germany at least, where VAT of nineteen percent would be due. These tax differences are also the reason why Tefaf, the world’s most important trade fair for old art, does not take place in Cologne, but rather in Maastricht in the Netherlands, where VAT at the fair was reduced from nineteen to six percent some years ago.

WELT: You are a chief lobbyist for the art trade in Europe. What do you request from Germany?

Hanstein: The British government intends to completely abolish import sales tax after Brexit. One answer would be to concentrate the import sales tax for art in Germany uniformly at seven percent. Then Germany could at least be compatible with its neighbouring countries.

WELT: In Great Britain, around 50 million pounds is taken in import sales tax on art each year. Revenue that London would then lose.

Hanstein: Yes, but the art trade in the UK has an annual turnover of over ten thousand million pounds and employs 100,000 people from picture framers to auctioneers. In London especially, the art trade is an important industry. The loss of import sales tax would be a “quantité négligeable”. In this respect, London can do away with it. A third of it is already import into the EU via London!

WELT: But even seven percent in Germany won’t help against zero percent VAT.

Hanstein: No. But at least the difference compared to the other important EU states would no longer be so great. And some foreign branches of a German gallery would be superfluous if we had a uniform import sales tax of seven percent. Germany would therefore gain more than they would lose, as would the art scene here.

WELT: Are they in talks with the Minister of State for Cultural Affairs, or has the dialogue reached a disjuncture since the controversy surrounding the Cultural Property Protection Act?

Hanstein: Naturally as art historians and dealers, we are friends of a Cultural Protection Act. But we voted against this act because we would prefer it to be less complicated and less bureaucratic. And collectors and dealers have caused the government to lose face because the constitutional complaint filed against the Cultural Protection Act was not completely without success. Experience to date should soon lead to an evaluation. Nevertheless, we would have welcomed it if the government had followed the proposal of the regulatory council and introduced a state preemption right. This would have been the ideal ruling, which works well in Great Britain, Benelux and France. And I have not yet heard any private collectors speak out against it.

WELT: Which arguments do you put forward in the evaluation of the Cultural Property Protection Act?

Hanstein: Apparently, we are the richest country in Europe, and culture is obviously of value to us. But why does the state want to intervene in our property in such a way that it almost resembles expropriation? Who buys a Golf that he can only drive in Lower Saxony? When the state wants to secure cultural goods for the general public, then it should also acquire them for the general public. However, the coordinates must then be adjusted: the amendment defines the term of cultural property more strictly than the old law. And there is a groundbreaking rule by the Federal Administrative Court on the entry of objects in the list. Accordingly, no comparable object can exist in a public museum. For example, they cannot protect a Beckmann or a Kirchner as there are enough representative important works by these artists in all major museums. In this respect, the all-clear must be given.

WELT: Why does the all-clear not reach the collectors though?

Hanstein: The owners of artworks simply want assurance that there is no danger that their cultural property could be put under protection and their assets reduced. But the government will not give this security clearly and unambiguously. This has also made the collectors outside of Germany very insecure.

WELT: Can you explain that?

Hanstein: When I acquire a painting by Brueghel in Belgium or the Netherlands for the auction, then there was the fear at first that one would need an export permit for the painting later. The countries have meanwhile made improvements and made it clear that a picture only needs this permission if it contributes to national identity. But if you bring a picture to Germany for a few weeks, to exhibit it before the auction, then the issue of national identity does not apply. In this respect, we can now tell our overseas customers that their picture is not subject to the Cultural Property Act. But this needs official clarification.

WELT: Have the collectors overreacted? Many have apparently taken their art out of the country, also on the advice of some auction houses.

Hanstein: As an art dealer, we underestimated the mentality of our clients and the sensitivity of the collector. This led to a flighty overreaction. Some brought their art to England and now have to quickly get it back because otherwise they may have to pay import sales tax after Brexit.

WELT: The state suggests that the art trade wants to conceal a great deal, such as the provenance of objects with a Nazi history or a colonial past. Can you understand the moral perspective?

Hanstein: No. I would not place morality above the law. For me, the law is codified morality. We live in a constitutional state. Lempertz was the first house in Germany to join the Art Loss Register. We wanted to be part of it to fulfil our due diligence obligations regarding provenance. It is still today an unsurpassable system. At the same time, the art market was proactive. After all, it is the museums that lag decades behind in provenance research. The art trade has been doing its homework for over forty years. If the government reproaches us in this respect, then perhaps it wishes to distract us from its own failures.

WELT: The art trade is also criticised for facilitating money laundering. Is the new EU money laundering directive the solution?

Hanstein: The Fifth European Money Laundering Directive wants to inhibit so-called “illicit trafficking” and prevent the movement of money as a result of drug trafficking and terrorism. That is correct in principle. In this sense, I have no problem with the fact that you are also subject to the art trade, as are all businesspeople. The principle of “know your customer” is the noblest thing one can do. We auctioneers have fewer problems there. We know our customers, but are unable to ask all those who register for an auction to partake in a Due Diligence control. They would rightly reply that they had not yet made a decision to buy. Interestingly, the Federal Government excludes itself from these duties of care: At state public auctions, verification does not take place until the hammer has gone down. That must also apply to us.

WELT: When does the EU legislation come into play?

Hanstein: The art trade must be prepared for this for all sales over 10,000 euro from the end of January 2020. Unfortunately, this law also brings a great deal of bureaucracy with it. Some things are hardly feasible. At an art fair, for example, where many dealers and gallerists make significant turnovers, the KYC principle can hardly be justified. They would have to ask customers to provide a copy of their ID, their tax number, and preferably contact their tax advisor and reference person at the bank in order to check whether they have acquired their money legally. Some customers would turn on their heel. Eighty percent of all European art dealerships are small businesses with few employees. How could they cope with the additional work?

WELT: Why does the state have the art trade so much on its mind? It isn’t an important branch of the economy.

Hanstein: I would also like to know the answer. Culturally, it is very important.

WELT: But with regards to Germany’s turnover, not so much.

Hanstein: Around 1.5 thousand million euro isn’t peanuts, is it? With regards to the art market, the politicians have been misinformed. They have literally talked their way into this affair. Take, for example, the European import legislation that will soon come into force. Then, everything that is imported into the European Union and is over 200 years old, must be checked to see whether it has been legally exported from its country of origin. This can still be traced back to the EU Commissioner Pierre Moscovici, who, like Monika Grütters, wanted to put a stop to the smuggling out of the Orient. Only that has just turned out to be incorrect. The German government’s Dark Field Study was a fiasco. At a cost of 1.2 million euro, it was established that the alleged smuggling of archaeological objects out of the Orient hardy takes place in our country. Thanks to the false assumptions that it is financed by terror organisations, the market for archaeological items is now dead, to the detriment of museums as well. All that could have been saved. Art dealers and gallerists are culture-supporters. The government should acknowledge that. Why does Germany only value art when it hangs in a museum?