Roman Zieglgänsberger – How Art Is Created

A Brief Comment on Max Pechstein’s Programmatic Painting „Self-Portrait, reclining”

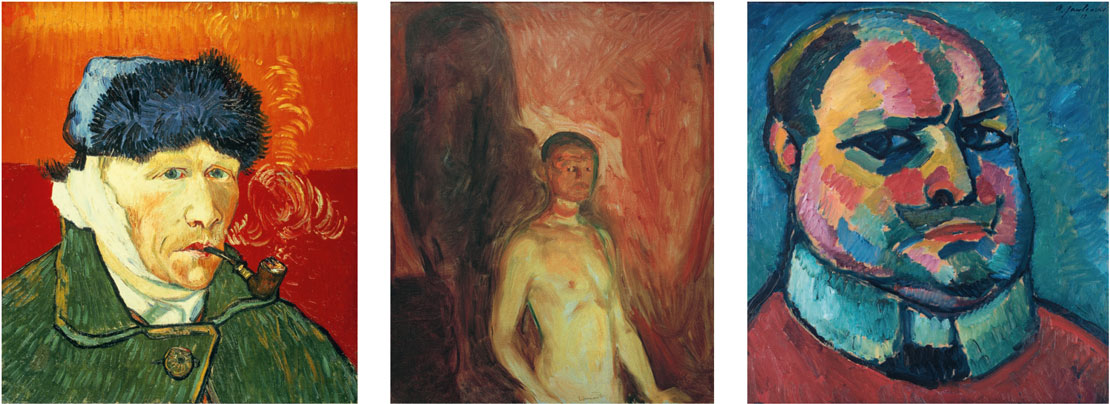

Painted in vivid colours with extraordinary vigour, “Self-Portrait, reclining” is an exceptional work. This is true in more ways than one. It is not just Pechstein’s first self-portrait – a fact that, all on its own, would already automatically secure it a special status within his oeuvre. This picture is also about more than just the artist presenting himself in his profession as a painter while achieving as precise a resemblance as possible. Instead, it shows how art is created. To be completely precise, it even shows where art is created. Thus, in terms of its aspirations, the painting takes its place among the greatest expressive self-portraits by painters like Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch and Alexej von Jawlensky (see figs. below). Van Gogh depicted himself with a smoking pipe to show how the artist’s mind would burn with passion as he painted and how this could sometimes lead him to harm himself. Munch had to first descend all the way down into Hell in order to know himself and confront his unfathomable themes. Jawlensky no longer presented anything except his round head, but it became a palette which allowed him to reassure himself that he and his paints, his painting, his actions had genuinely become one.

But, returning to the ingenious composition that Pechstein created at the precise moment when the artists of the “Brücke” group, which had been founded in Dresden in 1905, discovered their unmistakable style: how does it work?

Bandaged Ear and Pipe, 1889, Oil on canvas, 51 x 45 cm, Mary and Leigh Block, Museum of Art Chicago

Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait in Hell, 1903, Oil on canvas, 82 x 66 cm, Oslo, Munch-museet

Alexej von Jawlensky:

Self-Portrait, 1912, Oil on cardboard, 53.5 x 48.5 cm, Museum Wiesbaden

Max Pechstein presents himself here in full length: his figure extends across the entire image, propped only on his right elbow and left foot as he lies there creating a self-portrait, his gaze completely focused on what he is doing. Perhaps the painter is outdoors on a green lawn in front of the yellow wall of a house. However, what is decisive for the painting’s thematic message is that the palette is found at the edge, all the way to the left, and the depicted portion of the canvas is opposite it, at the furthest possible point to the right. This is where the “Self-Portrait, reclining” that we ultimately have before our eyes is being created. Another subtle touch is that the painting has (as is only logical) been done in exactly the same colours which are to be found on his palette. This means that Pechstein, in transferring the colours from the palette on the left to the canvas on the right, is executing an “artful” balancing act before our eyes. The primary colours red–yellow–blue as well as the secondary colour green on the palette have to be “translated” into the art on the canvas by the artist who only visibly stands (or, in our case, “lies”) at the centre of the work in the self-portrait. Reading the picture from left to right, in the direction of Western writing, we see – through Pechstein – how art is created, specifically: the colours are used to precisely capture the motif and to realise it on the canvas through the tremendous efforts of the artist, who is not just the creator but simultaneously the subject of the image here.

Once we have visualised the complex structure of “Self-Portrait, reclining”, it becomes clear that Pechstein understood this “process of becoming art” – carried out and exemplified here in an experimental apparatus utilising his own person – not just as a maxim for this one self-portrait but as applying to his entire future oeuvre as well. For Pechstein the body of the painter was accordingly the medium, the resonance chamber, through which the outwardly perceived subject matter first had to pass in order to become art. He is thus saying that the world has to be perceived with all our senses in order to ultimately – intermixed with the individual personality of the artist – be capable of becoming emotional art. Art is not just mind, art is not just the act of painting – art is plainly a matter of the “whole body”. A painting could not be more programmatic.