Alexej von Jawlensky

Heilandsgesicht

Circa 1919

Oil on firm paper with linen structure (36.6/36.9 x 26.2/26.7 cm), mounted on card painted in black 38.4 x 28.1 cm Framed. Monogrammed 'A.J.' lower left in light grey.

The outbreak of the First World War meant that Jawlensky was forced to leave Germany; he resettled in Switzerland - in St Prex, on the shores of Lake Geneva - where he created the first of his major series of paintings, the “Variationen” on a landscape motif. Beginning with the impression of nature provided by the view framed through his window, he cycled through variations on an underlying form secured in its focus, composition and detail; in his art it tended to become ever more “pure” and more abstract in the sense of a formal essence. His aim was a substantial concentration and expression of an “inner necessity”, which was also to result in a corresponding resonance and clear reception in his audience, the viewers of his art. Each individual masterpiece approached ideally towards an “Urbild” or “primeval image” (see Clemens Weiler, Alexej Jawlensky, Köln 1959, pp. 91 ff., p. 96). Similar processes of artistic formation underlie subsequent series created shortly thereafter in Switzerland - the “Mystische Köpfe”, “Heilandsgesichter” and “Abstrakte Köpfe” - and finally also the “Meditationen” (comparative illus. 6), from his late work in Wiesbaden, which glowed ever more intensely and became more and more symbol-like.

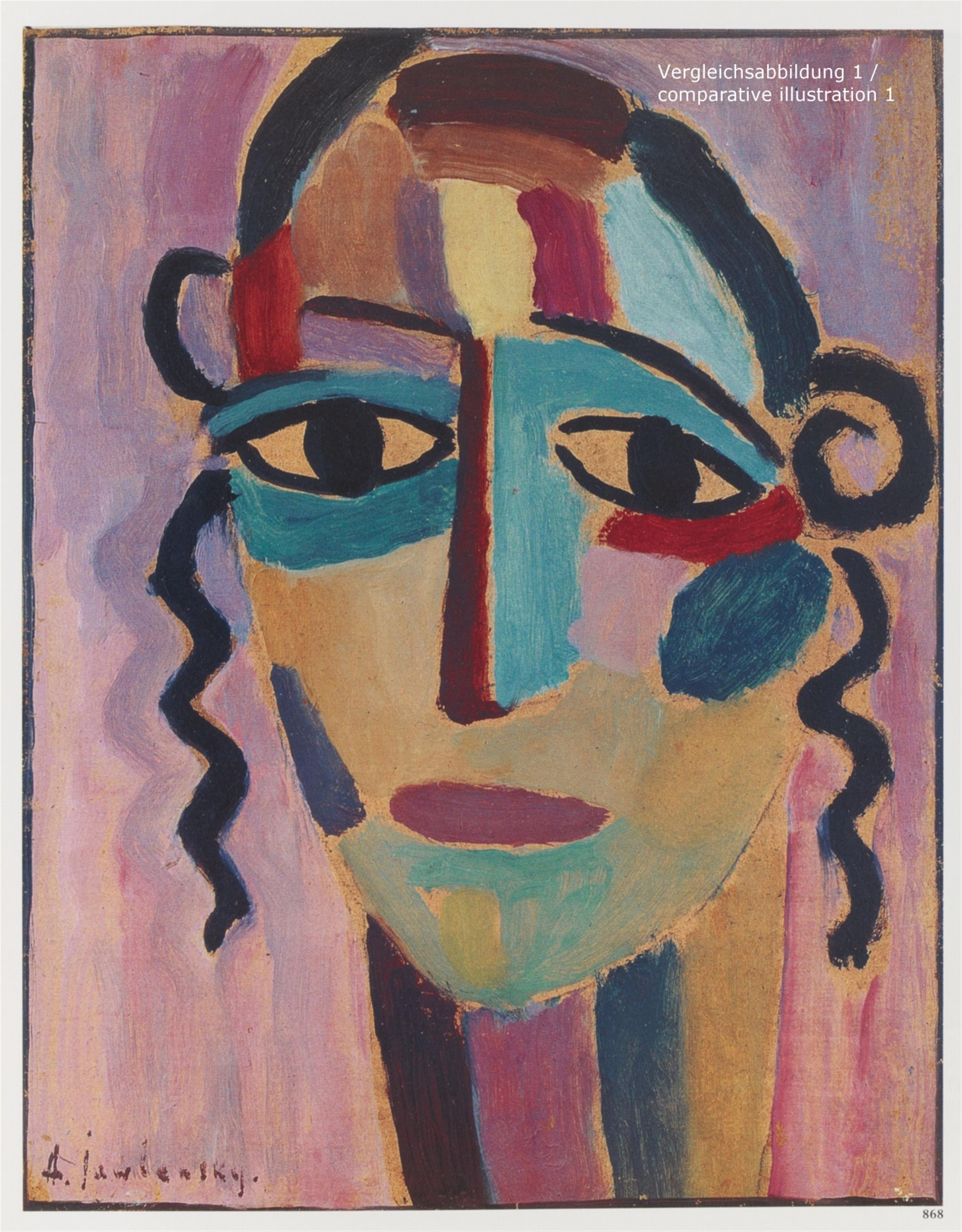

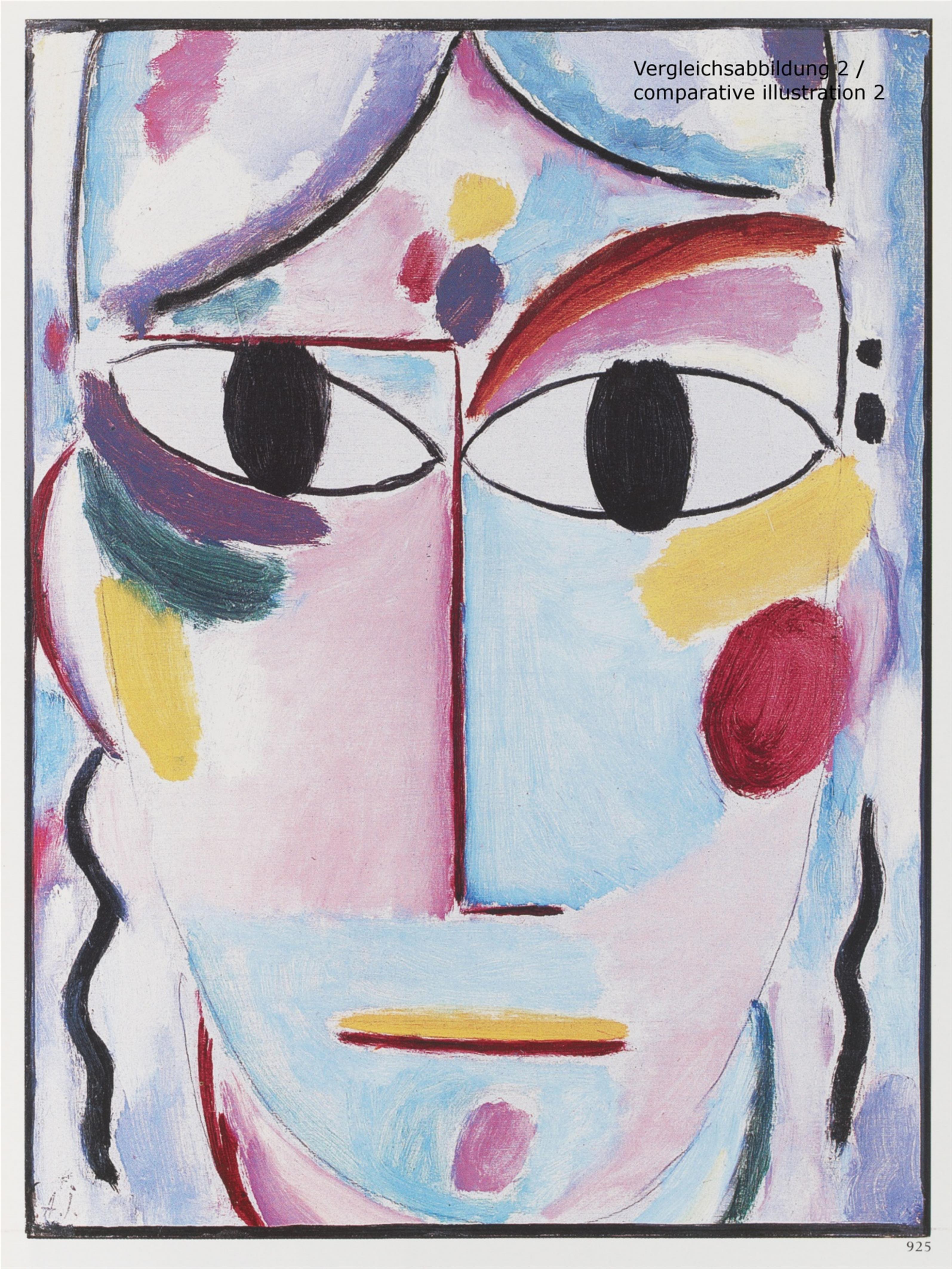

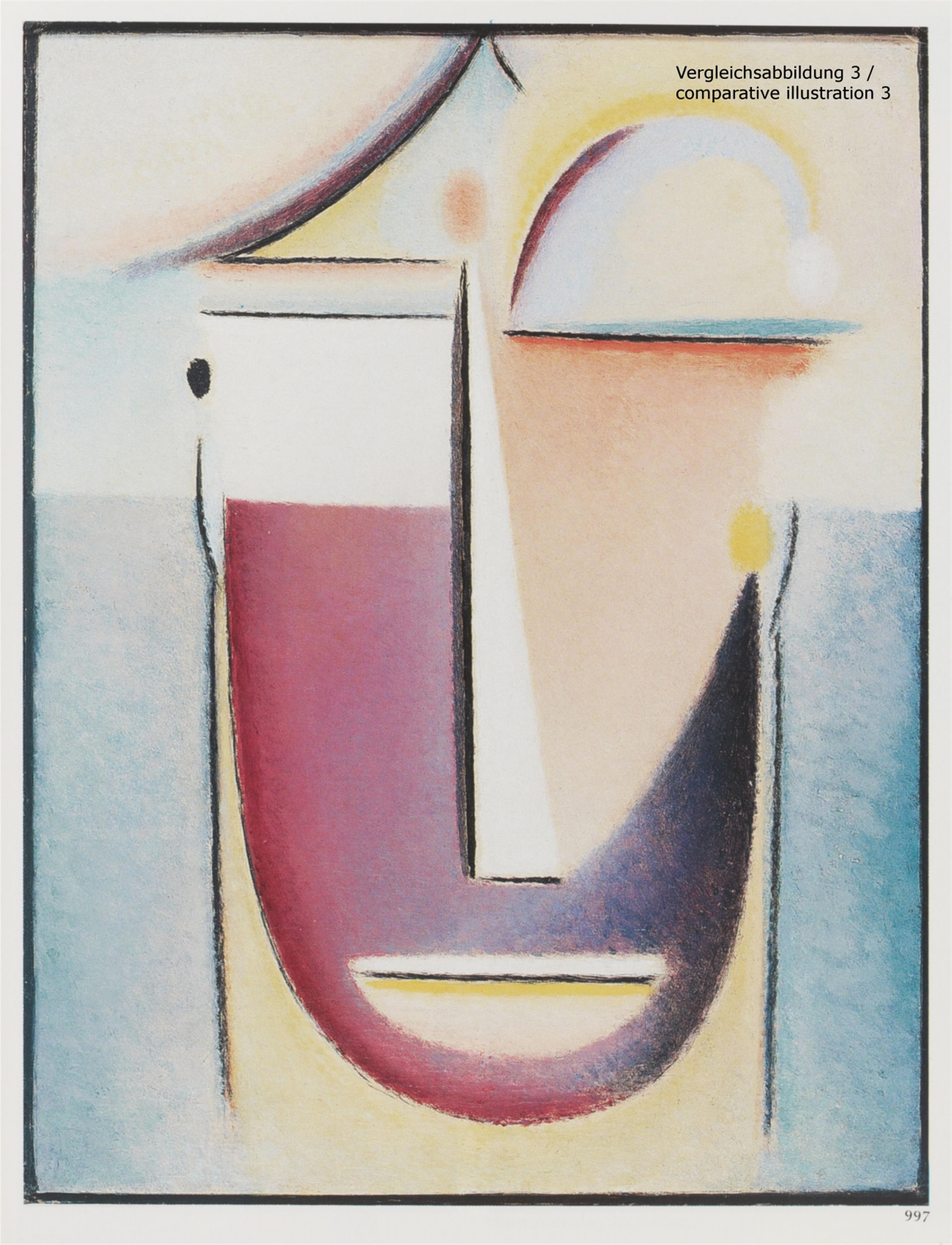

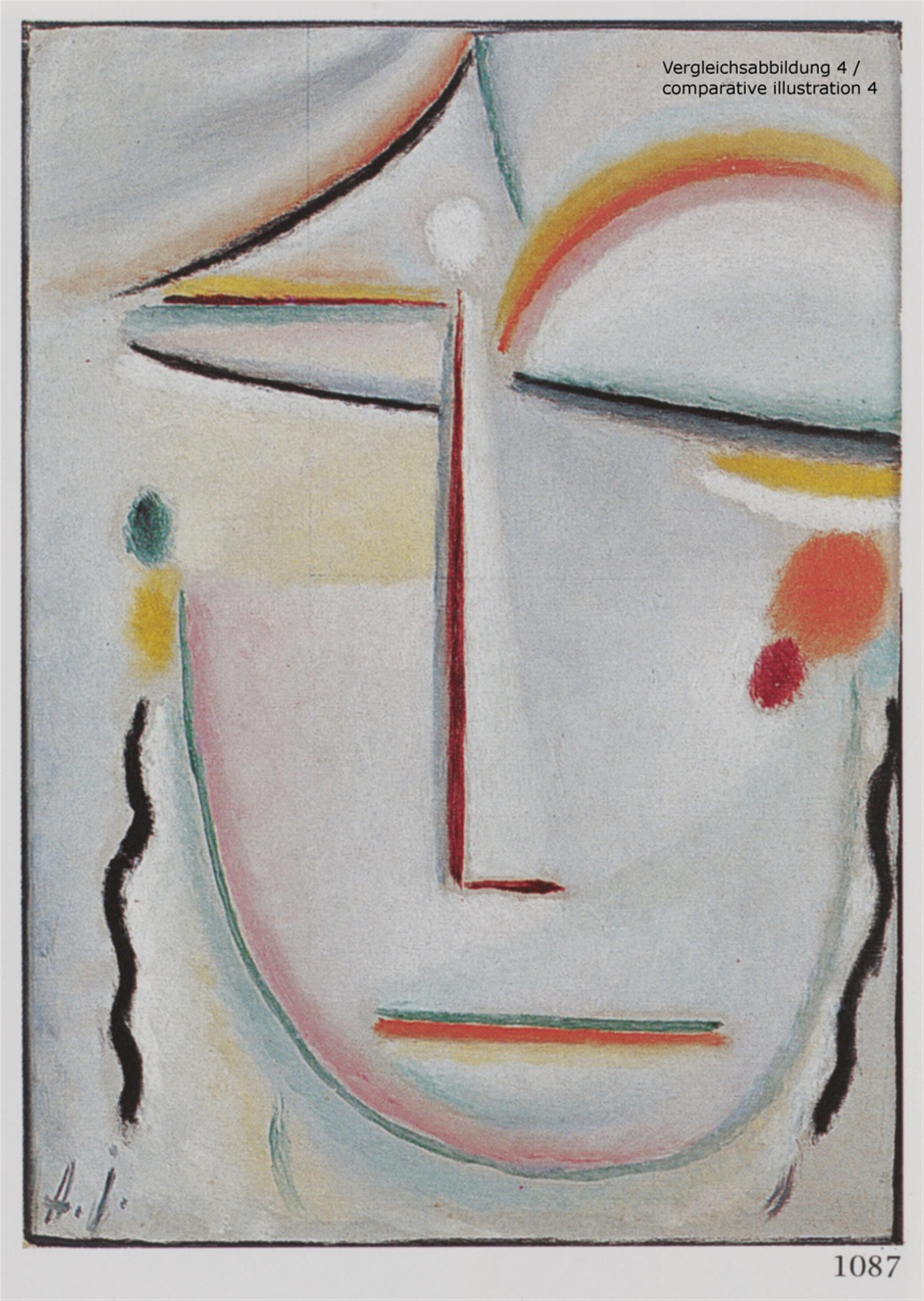

Our extraordinary and unique “Heilandsgesicht” from around 1919 displays its kinship and differences relative to all the other comparable works from these series: turning back to the human face as a subject in 1917, Jawlensky initially portrayed Emmy Scheyer, for example, multiple times. With the individual portrait as his starting point, her semi-abstract likeness metamorphosed into the “Mystischer Kopf”, however, this still has something natural and anatomical about it (comparative illus. 1). Before the end of that year he created the first, early formulation of the theme “Heilandsgesicht” (comparative illus. 2), which - laid down with a freer and more painterly brushstroke - is of an entirely different expressive substance than our work, but features the decisive development towards the “open eyes” and the new, strictly frontally conceived symmetry. The next step was Jawlensky's development of the composition “Abstrakter Kopf: Urform” (comparative illus. 3), of 1918. In the twenties this strongly mathematical and geometricised version would become the dominant underlying form in his oeuvre (comparative illus. 5). In this respect our “Heilandsgesicht”, with its delicately applied colours, is related to the bright transparency of “Erleuchtung” (comparative illus. 4), which was created in 1919; in terms of its structure, it mediates between these different exemplary formal positions.

Clemens Weiler has aptly described the transitions and connections between these series of works:

“With the variations Jawlensky had equipped himself with the means to find the cryptographic symbol for the inner resonance of a natural being. It was only logical that he was able to depict the harmony he had striven to attain through years of constant practice solely in the human face, because there lies the only realm where inside and outside, individual and world, nature and soul meet, where 'religion' - in the truest sense of the word - occurs. However, this human countenance could only be one in which the entirely personal fortunes had been elevated to a universal human significance transcending the individual. The abstraction necessarily linked with this was not a process based on elimination or even sublimation, but on potentiation. The pictorial cypher that emerged was not the result of an abstraction drawn out from the outside and by means of logic, but of a concentration pursued from within. The 'Heiligengesichte' and then 'Heilandsgesichte' came about in this way. Jawlensky himself wrote about this: 'I painted these variations for several years, and then I had the need to find a form for the face, because I had understood that great art should only be painted with religious feeling. And I could only bring that to the human countenance. I understood that the artist, with his art, has to use forms and colours to say that which is divine within him. This is why the artwork is a visible God and art is “longing for God”.' C.G. Jung has depicted how Christ visualises the archetype of the self, that is, how he represents the entirety of the individual human being and, in this way, all humanity - everything which bears a human face. Jawlensky found the synthesis constantly sought by him and his circle in the figure of Christ.” (Clemens Weiler 1959, op. cit. pp. 102/103).

Our version of the “Heilandsgesicht” displays an unusually strong expressiveness in the formulation of the passage around the eyes, which has qualities that can be experienced as a “holy” look, as an almost communicatively implied gaze. In a religious context, Jawlensky's “Heilandsgesichter” are reminiscent not just of Russian icons, but also of the auric art of the early Romanesque period, with its elongated figural proportions. However, Clemens Weiler states: “The old icon was the image of an idea that transcended the individual and, precisely for this reason, it actually always had to remain unchanged. In this sense Jawlensky's image of Christ is not an icon.” (Clemens Weiler 1959, op. cit., p. 103).

Emmy Scheyer grasped things in a different way, removed from faith but nonetheless universal: “Jawlensky transposed the human head as such into a language of abstract life, drew it up out of its earthly existence in order to manifest the soul and spirit. The new laws which he found in this way are mathematical. He assimilated the laws of the other arts into his pictures: architecture in the balancing of the colours, music in the sonorous rhythm of the colours, dance as the line of the colours, sculpture as the form of the colours, poetry as content or as the word proclaimed by the colours, but painting as their symphonic summation.” (cited in Clemens Weiler 1959, op. cit., p. 106).

Catalogue Raisonné

M. Jawlensky/ Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky/A. Jawlensky 1081

Certificate

We would like to thank Angelica Jawlensky, Muralto, for kind information.

Provenance

Probably Nina Kandinsky; Frankfurter Kunstkabinett, Hanna Bekker vom Rath (acquired there in 1955); since then in family possession, Private collection, Switzerland

Exhibitions

Zurich/ Lausanne/ Duisburg 2000/ 2001 (Kunsthaus Zürich/ Fondation de l'Hermitage/ Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum ), Jawlensky in der Schweiz, without cat. no. with colour illus.