Leo von Klenze

Roman Architectural Veduta with the Cloaca Maxima

Oil on copper. 56.5 x 44.5 cm.

Norbert Lieb begins his catalgoue raisonné of the works of Leo von Klenze, still considered a seminal publication to this day, with the following statement: “When a Neoclassical architect is also active as an artist, in free-hand drawing and panel painting, this appears to contradict contemporary ideas regarding stylistic eras and the division of artistic genres. The biographies of Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin and Klenze in Munich, both of whom combined the work of architect and painter, represent a phenomenon that is worthy of and demands further investigation.”

One recognises several parallels between the lives of Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781 - 1841) and the slightly younger artist Leo von Klenze (1784 - 1864). Schinkel studied under Friedrich Gilly and his father David Gilly, head of the Berlin Architectural Academy. At the age of just 16, Klenze began his studies at the same institution and completed his training at a remarkable pace, writing his final exam in 1803 at the age of 19. Schinkel and Klenze both shared a passion for Italy, a love that would reveal itself repeatedly in their drawings and studies of ancient Greek and Roman ruins. These formed the foundation for the architectural designs and constructions of both Neoclassicists, and would have a lasting impact on the skylines of Berlin and Munich respectively. However, what distinguished the two artists was Schinkel's romantic admiration of the Gothic architectural style, which Klenze firmly rejected. While Schinkel remained captivated by the austerity of the North, Klenze absorbed a certain southern, Italian, quality. This may have been due to his more than 20 journeys to the south, but also to his close connections to the circle of artists and confidants surrounding his patron, Crown Prince Ludwig, the later King Ludwig I.

The atmosphere of those stays in Rome is captured in a famous painting by Franz Ludwig Catel (fig. 1), showing the Crown Prince feasting in a Spanish wine tavern with the illustrious group of travellers, artists, and advisors who accompanied the future king to Italy in 1823. It was commissioned by the Crown Prince in 1824 and is now housed in the Neue Pinakothek in Munich. In a letter to the collector and critic Gottlob von Quandt, Catel describes the exuberant situation as follows: "Recently I finished a small Bamboccianti picture for the Crown Prince of Bavaria. His Royal Highness had graciously organized a small déjeuner on Ripa Grande at Don Raffaele to say goodbye to Herr von Klenze and instructed me to immortalize the scene with my brush. From left to right the following are depicted: The landlord, Crown Prince Ludwig, Berthel Thorvaldsen, Leo von Klenze, Count Seinsheim, Johann Martin Wagner (standing), Philipp Veit, Dr. Ringseis (standing), Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Catel, Baron Gumppenberg. Through the open door one sees the Aventine beyond the Tiber. [...]"

Klenze received his training as a draughtsman and painter under Constant Bourgois, a pupil of Jacques Louis David during his first stay in Paris in 1805. But it was not until 1824 that he exhibited his first drawings at the Münchener Kunstverein, these were followed two years later by two paintings at the same location - including the present work, painted in Rome in 1824/25. In this early work, Klenze, who was highly knowledgeable in ancient buildings, depicts a very unusual subject: The "Cloaca maxima", the main artery of the ancient sewage system built in the 6th century BC. It was used to drain the hollow between Palatine and Capitol, the later Forum Romanum.

Klenze would not be Klenze, the architect, if he did not transfer the place above the canal system with the ruins of the basilicas, temples and triumphal arches hundreds of years later into modern times with newly constructed Romanesque and Renaissance buildings. The painter integrates the ancient, imposing round arch into the system of the "Cloaca maxima", overgrown with lush vegetation and covered with a high wall. The building to the right illustrates the next step in architectural development on the way to the Renaissance: The covered window construction and slightly inclined hipped roof are an indication of the coming renewal. This architectural journey through time is continued with the construction of a supporting scaffold, an open roof truss above a building, which here is concealed by an early Christian chapel, of which we see a small section of a portico. Only the remnants of vaulting on the outer wall of the building point to its function as a sacred space.

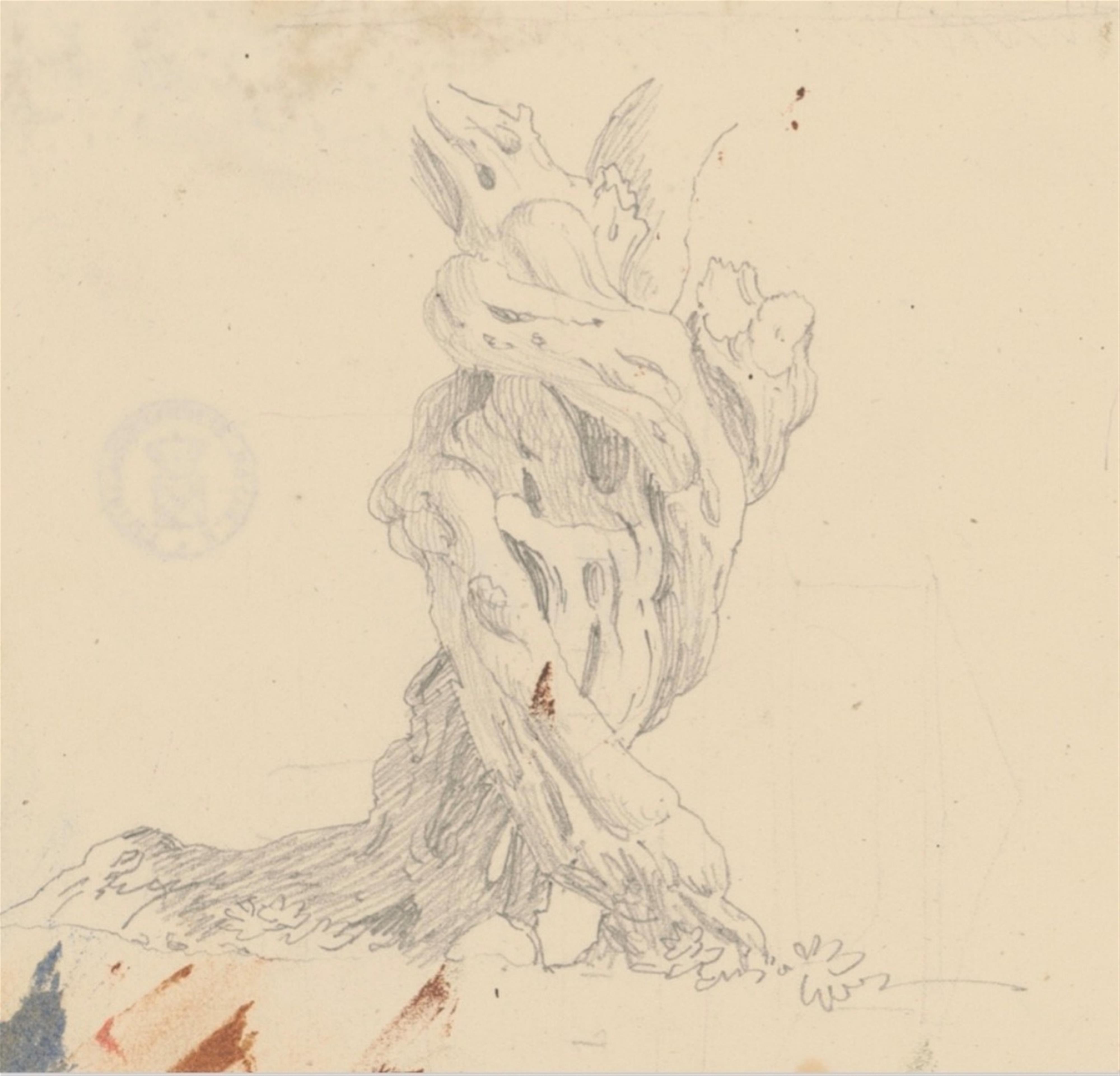

Klenze has captured a view of a slightly rugged patch of land framed by architecture on all sides and illuminated by afternoon sunlight from the upper left. A curving path leads up to the shaded entranceway of the “Cloaca maxima”, passing by a mascaron fountain reminiscent of the “Bocca della Verità”. This ancient round relief depicting the “Mouth of Truth” is around 2000 years old but is first documented in around 1485 and has been housed in the portico of the Church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin since 1632. In his work, Klenze places the fountain amid the weeds and ivy growing between the cracks of the ancient wall. The overgrown natural roof of the ruin is crowned by an old olive tree whose strikingly twisted trunk Klenze discovered in Agrigento in Sicily and sketched on 30th December 1823 (fig. 2).

Klenze combines the disparate motifs of the entrance to the "Cloaca maxima", the "Bocca della Verità", the olive tree, and the architectural styles of various centuries into a carefully arranged architectural composition. He also uses figural staffage to enliven the scene. The woman washing at the fountain and the figures climbing up the winding path or along the riverbed serve to both bring life to the picture and clarify the proportions and depth of the space. Only the lone man thoughtfully observing the genius of the place, the architecture, and the hustle and bustle appears different: A conspicuously dressed gentleman with in a top hat. In this figure Klenze seems to anticipate the characteristic scenes painted by Carl Spitzweg several decades later. Lieb believes that Klenze may have eternalised his old friend Johann Martin von Wagner in this slightly caricatured figure. Wagner, who was a painter, sculptor, and art collector as well as being King Ludwig's art agent in Rome, was an important Cicerone and teacher for Klenze.

This work, in which Leo von Klenze combines various motifs and encounters, illustrates a principle already applied with great success by Caspar David Friedrich to conjure up a romantic illusion. Klenze also sought to invoke a subjective vision of reality within a simple architectural history. The architecture is caught between two poles of objective fidelity with veduta painting on the one end and artistic composition on the other. Although “Cloaca maxima” is one of Klenze's earliest works it immediately illustrates his exceptional talent for rendering colour, light, and space. The author, art historian, and folklorist Max Schottky wrote of Klenze's work as a painter in 1833: “Privy Councillor von Klenze is not only known as one of the most famous living architects, but also excelled so highly as a pictorial artist that one can only lament the fact that his most important offices so often pulled him away from this, his favourite art form.”

Provenance

Ludwig Lange (1808-1868), painter and professor of architecture in Munich. - Ernst E. Voigt (1838 - 1921) and his wife Eugenie Lange (1844 - 1929), who inherited the painting from her father. - By descent in the possession of the Voit family until the present owner. - Private ownership, Belgium.

Literature

Jahresbericht über den Bestand und das Wirken des Kunstvereins in München, Munich 1825, p. 17, no. 228. - N. Lieb. F. Hufnagl: Leon von Klenze, Munich 1979, p. 76, no. G. 3.