An opulent Berlin chandelier

Gilt and silver-plated bronze and metal, cut clear and cobalt glass. Eight-flame chandelier with pierced drip pans suspending lamps in the upper section, below it two smaller pierced rings, the central one of which with a horizontal blue glass disc. The blue central spindle surrounded by eight chains, above it a further curved ring suspending eight lamps. Hung from four chains. All rings, drip pans and lamps fully hung with largely original droplets. The central spindle restored, the chain connecting to the central spindle replaced, the drip pan below it presumably a later addition, the fine strand of beads surrounding it and the rhomboid droplets presumably also. H c. 150, W 81 cm.

Berlin, attributed to Bronzewarenfabrik Christian Gottlob Werner & Gottfried Mieth, c. 1797 - 1815.

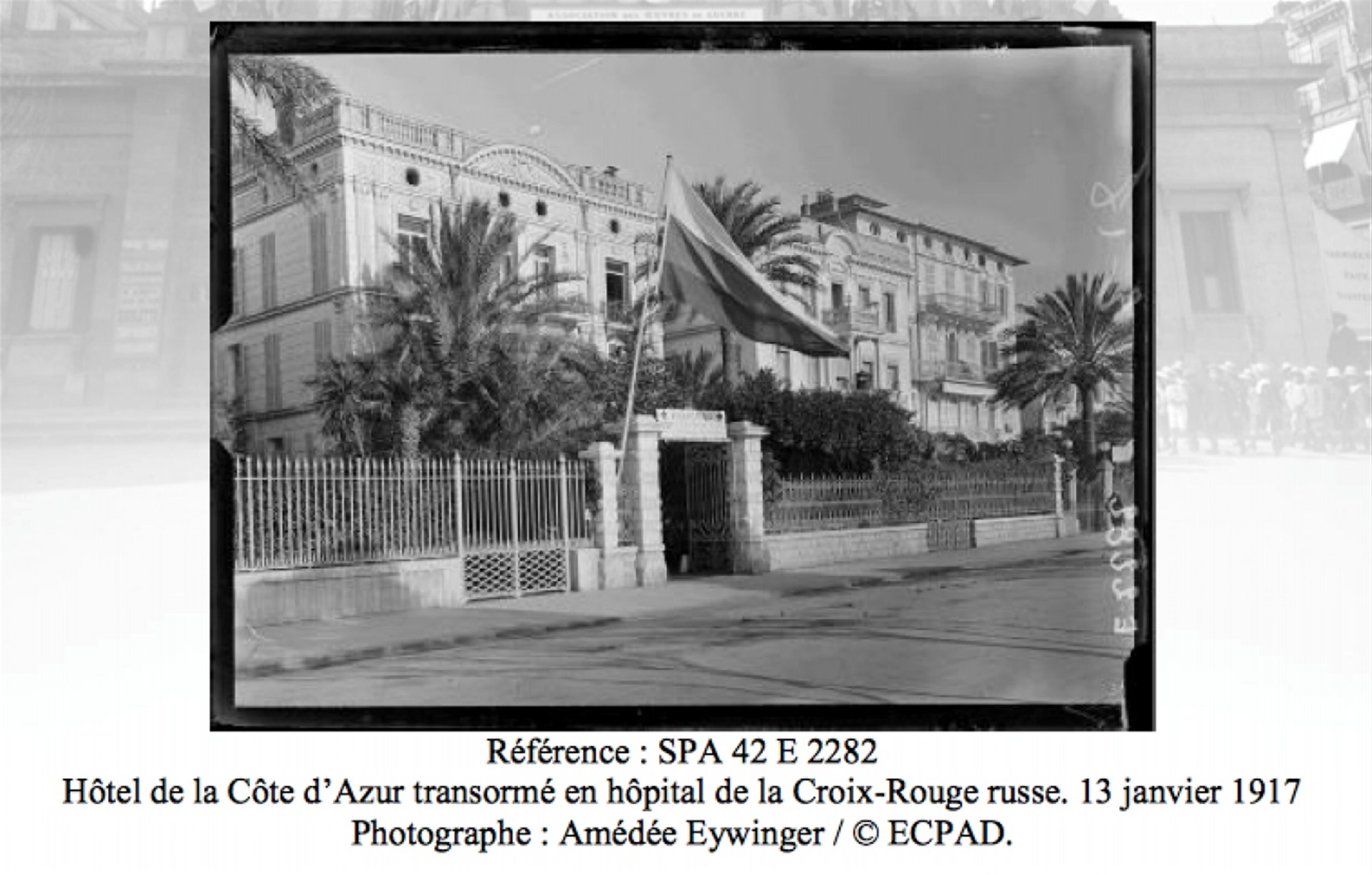

The two Berlin-born bronze casters Christian Gottlieb Werner and Gottfried Mieth began their careers in the Royal Berlin Porcelain Manufactory as modellers and embossers. In 1791, they went into business for themselves with the idea of a "Bronze und Kunstsachen Fabrik" (bronze and art objects factory) and founded a partnership together with the master brass caster Friedrich Luckau jun. The workshop was located in Leipziger Strasse, and in 1801 they moved into a building in Jägerstrasse. The special quality of the products was aimed at an international, wealthy, aristocratic clientele. Werner and Mieth probably owe most of the popularity of their chandeliers to an order placed by Wilhelmine von Lichtenau, the mistress of King Friedrich Wilhelm II, who, known for her good taste, was allowed to help decorate several royal residences. This is perhaps how the variant of this chandelier came to be in the winter chambers of King Frederick William II in Charlottenburg Palace (East Indian Zitz Room, room 348). The model presented here was offered and produced in the variations mentioned below in the period between 1797 and 1815. Compared to other versions, it impresses with its considerable size. Two densely hung hoops are staggered under the main hoop, and there is also another hoop on top with full tassel hangings and attachments. A very nice detail is the suspended vase-shaped glass element, which does not play a supporting role in the architecture of the chandelier, but centres it visually. It corresponds with the blue glass pane, which is suspended from the bottom of the second hoop and, when illuminated, is reminiscent of the blue firmament. The original silver-plated metal rods and the silver-plated finial rose are extremely rarely preserved. These elements were usually mistakenly re-gilded in later times. The silver-plating served to increase transparency, in contrast to the gilding, which reflects the light more strongly and differently and is perceived more as a contrast to the glass hanging. The provenance of the chandelier has been recorded since the previous owners Prince Ernst II zu Hohelohe-Langenburg (1863 - 1950) and Princess Alexandra (born Princess Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, 1878 - 1942). Before the First World War, they lived in a magnificent, spacious villa in the hills above Nice, which is referred to in Hohenloh's archive documents as "Schloss Fabrou" or "Villa Fabrou" and which included a beach house on the Promenade des Anglais. The chandelier hung in this building until it was demolished in 1954, presumably in the large salon on the upper floor, which offered a view of the sea. In 1914, both villas were confiscated by the French state as "Bien de Guerre". While the Villa Fabrou was later to be sold to the Romanian king, the beach house was used from 4th December 1914 and until 1918 as a "Hôpital russe" for the care and rehabilitation of Russian casualties of the First World War. In 1934, the buildings were acquired by Antoine Gianotti (1871-1948). He was a deputy in the Alpes Maritimes department from 1928 to 1932, then a senator until 1939. After the Second World War, both houses passed into other private ownership.

Provenance

Verifiably in the possession of the Princes zu Hohenlohe-Langenburg as of 1896. Property of the French state (confiscation as “Bien de Guerre”) in Nizza in 1918. This property acquired in 1934 by Antoine Gianotti (1871 – 1948). In private owership since 1948. In Swiss private ownership since 2015.

Literature

We would like to thank Birgit Kropmanns for providing the information about the bronze manufactory (Klappenbach, Kronleuchter des 17. Bis 20. Jahrhunderts aus Messing, „bronze doré“, Zinkguss, Porzellan, Geweih, Bernstein und Glas, Berlin-Brandenburg-Regensburg 2019, p. 190 ff.). For more on the building see Kanossian, Les Russes sur la Coôte d´azur pendant la Grande Guerre, in: Miscellanées Franco-Russes, November 2018: “À Nice, la villa de Hohenlohe est séquestrée en octobre 1914. Située au 73, promenade des Anglais, elle comporte deux étages, est dotée d’un grand jardin et d’une maison de concierge. Elle est attribuée au comité directeur de l’hôpital russe pour les blessés militaires, afin de former l’hôpital bénévole n° 139bis à Nice, alias hôpital russe. L’hôpital compte entre vingt et vingt-quatre lits. Il est destiné au soin des officiers. Il accueille ses premiers blessés le 14 décembre 1914 ; les derniers le quittent le 30 avril 1919. Fermé au cours de l’été 1917 en raison de la canicule, l’hôpital est réouvert le 4 novembre 1917 (37) L’hôpital est inauguré le 1er décembre 1914 en présence du clergé russe, des autorités civiles et militaires et de la communauté russe de Nice (38). Les salles ou chambres sont nommées de vocables prestigieux ou traduisant les alliances militaires : « salle grand-duc Nicolas », « salle Poincaré », « salle princesse Youriewski », « salle Albert Ier », « salle George V », « salle Joffre » (39). Les maladies ou blessures sont très diverses : fractures, dyspepsie, paludisme, bronchite, intoxication par gaz… En près de cinq ans, ce sont cinq cent douze officiers qui y sont hospitalisés. Le personnel est mal connu. La princesse Marie Ouroussoff, chef infirmière, est citée à l’envi par la presse. Entre 1915 et 1917, on dénombre vingt infirmiers. Le docteur Wladimir Walter, né en Russie et naturalisé français en 1914, y exerce de février 1915 à avril 1919. Outre les subventions, l’hôpital russe compte sur la générosité publique. La presse s’en fait le témoin. À la fin de janvier 1915, le prince Serge Galitzine, grand veneur de l’Empereur de Russie, en séjour à Nice, souscrit deux lits pour la princesse et lui. En février 1915, la société des bains de mer de Monaco fait un don de mille francs. En novembre 1917, c’est la princesse Wiazemsky-Markov qui donne à son tour mille francs. L’hôpital est choyé par l’aristocratie russe de Nice. Le 13 décembre 1914, le château de Valrose accueille la matinée de l’hôpital russe de Nice. Une pièce russe est jouée par l’amirale de Solowtzoff, MM. Grigorioff et Michailowitch. Une scène d’Alceste est interprétée par Félia Litvinne et M. Ramoin, de l’Opéra de Nice, avec M. Miranne à la baguette. Enfin Félia Litvinne entonne les hymnes alliés. Concerts et cérémonies se multiplient à l’hôpital pour la collecte de fonds, notamment à l’occasion du Nouvel An russe : ainsi ce thé-concert en janvier 1915, ou cette matinée de bienfaisance, un an plus tard, au cours de laquelle une coupe de champagne s’adjuge cinq cents francs, ou encore cette fête en janvier 1917. Après la révolution russe, une controverse agite l’hôpital. Des tensions naissent, au printemps 1918, entre administrateurs. Une enquête de police est discrètement menée. Elle révèle en mai 1918 que les Russes ne versent plus de contribution ; ils commettent aussi des détournements : ainsi une partie des dons et subventions fait-elle fonctionner les soupes populaires à l’intention des Russes ruinés par la perte de leurs biens en octobre 1917. Finalement, le 19 juin 1919, le comité de l’hôpital russe procède à la dissolution de l’œuvre. (…)”