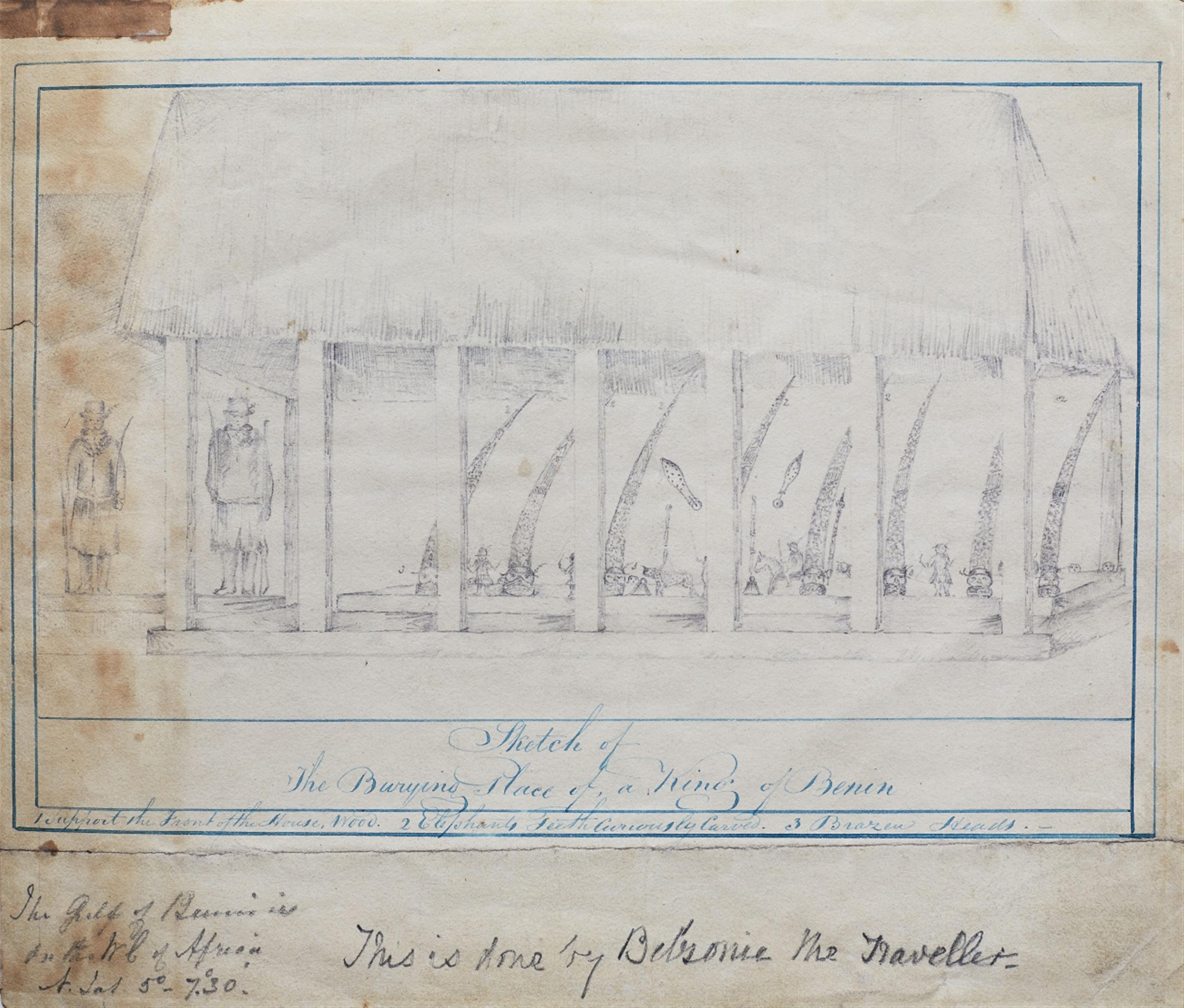

SKETCH OF THE BURYING PLACE OF A KING OF BENIN

A unique drawing of a royal ancestor altar at Benin, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778-1823)

23 x 27 cm.

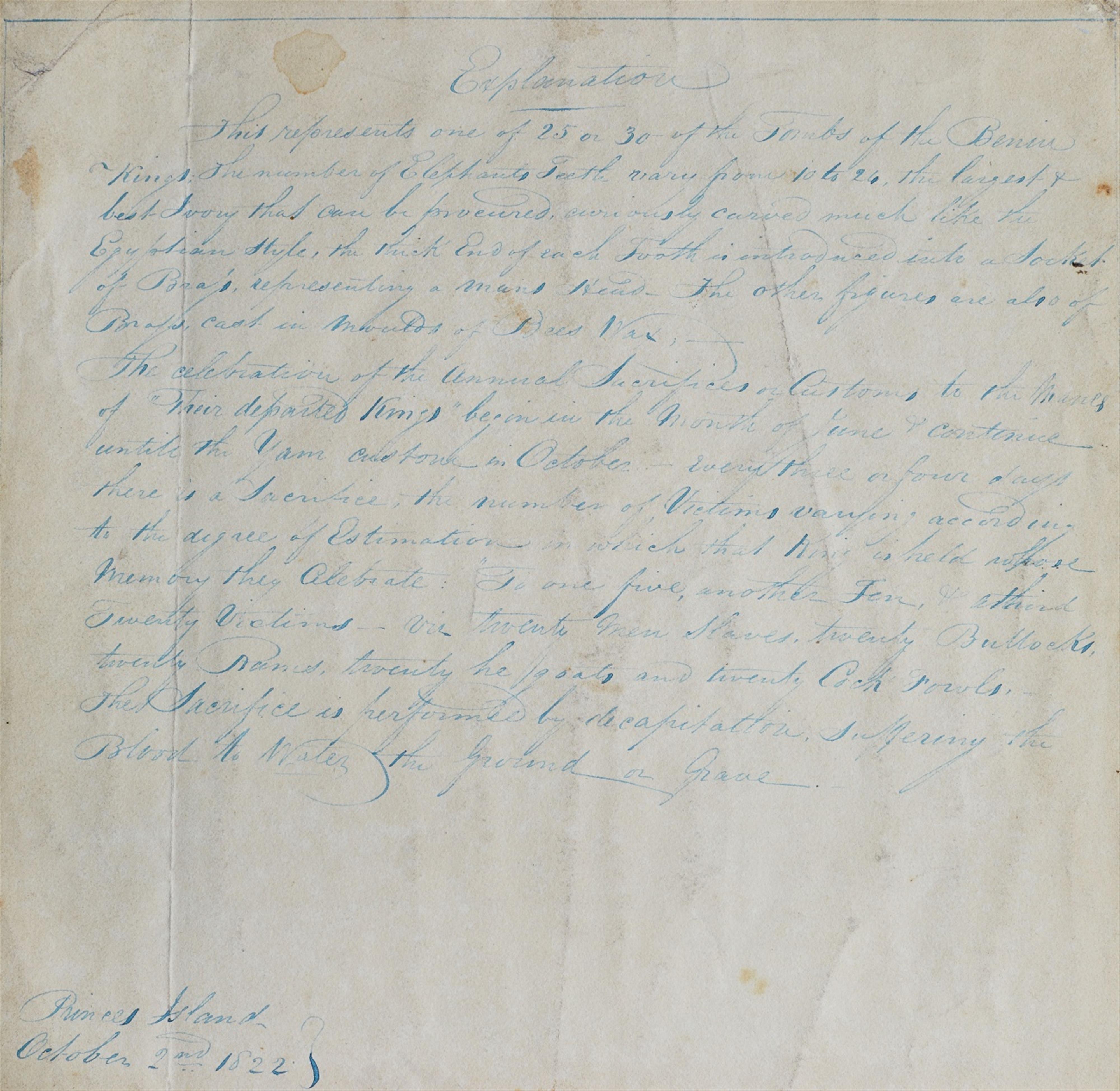

On the reverse of the drawing is the following legend in the handwriting of Giovanni Battista Belzoni:

Explanation. This represents one of 25 or 30 of the Tombs of the Benin Kings; the number of Elephants Teeth vary from 10 to 24, the largest & best Ivory that can be procured, curiously carved much like the Egyptian style, the thick End of each Tooth is introduced into a Socket of Brass, representing a mans Head. The other figures are also of Brass, cast in moulds of Bees Wax, -

The celebration of the Annual Sacrifices or Customs to the Manes of “Their departed Kings” begin in the Month of June & continue until the Yam custom in October — every three or four days there is a Sacrifice, the number of Victims varying according to the degree of Estimation in which that King is held whose memory they Celebrate: “To one five, another Ten, & a third Twenty Victims — viz. twenty men Slaves, twenty Bullocks, twenty Rams, twenty he goats and twenty Cock Fowls, — The Sacrifice is performed by decapitation, suffering the Blood to Water the Ground or Grave. Princes Island. October 2nd, 1822

Writing about the present lot in Christie’s catalogue in 1977 William Fagg states:

Belzoni was a renowned explorer, hydraulic engineer and showman who began his career as a circus strong man (he was six feet six inches in height and broad in proportion) and went on to make many of the most important discoveries in that great age of Egyptian exploration. Many colossal figures and fragments brought back by him grace the British Museum, the Louvre and elsewhere, and he is especially associated with the discovery and first clearing of the temples at Abu Simbel. See S. Mayes, The Great Belzoni, London 1959. In 1823 he conceived the idea of being the first white man to visit Timbuktu and of tracing the lower course of the Niger, still unknown, after Mungo Park’s death at Bussa in 1805. Baulked of progress through Morocco and Sierra Leone, he went around the coast to Cape Coast Castle and thence to the Benin River. Going up to Benin City by way of its river port of Gwato (Ughoton), he obtained an escort to Hausaland from the Oba and set out, but went down the next day with dysentry, was carried back to Gwato and died there on the afternoon of 3 December, 1823.

Considerable research has been carried out on this drawing. It was first established beyond doubt that the legend is in Belzoni’s fine hand, but there was doubt whether the drawing was an original by him or by another, or was a copy by him of another’s original. While research is not yet complete, the last appears to be the most likely and the most probable observer is Lieut. John King, R.N., whom Belzoni almost certainly met at Cape Coast Castle between 15 and 23 October, 1823, and whose experience and advice would have been most valuable to him since he had been to Benin City in 1820 (see account of his experiences in French, in the third person, in Journal des Voyages, Vol. XIII, Paris, 1823).

The importance of the drawing and its legend can hardly be over estimated. It is thought to be the only Benin drawing extant from before 1890, and undistorted by the engraver’s ethnocentric art. Perhaps the first thing to be noticed is the firm statement in the title that it represents ‘the burying place of a King of Benin’. While this is not quite certainly correct, it is a very plausible notion which does not seem to have been entertained by modern researchers, eve by the late Dr. R.E. Bradbury, (It is however also mentioned in the French account of King’s visit to Benin.) The practice may have ceased or changed in this century. If we turn to the objects shown on the altar, some of them are of types that have not previously been recorded as placed on the ancestor altars, even by the Expedition of 1897, which was usually careful to preserve information; among these are two leopards, a horseman, and standing figures of men (probably messengers bearing crosses). The heads have projections from the headdresses suggesting that they are of the type said to have been introduced by Oba Osemwede, who at the time this drawing was made had been on the throne four to six years; this tomb-altar may therefore be that of his father Obanosa. The two heads at the left show an exaggeration of the extent to which the coral choker by this time often covered the mouth, a feature which would be very striking to a European.

The living figures of guards to the left of the altar are wearing billycock hats, presumably of European origin. Finally, the statement that in about 1820 there were 25 or 30 such tombs shows that (after a bitter civil war) they were still kept up for all or nearly all the Obas - Osemwede was the 34th - whereas by 1897, according to the present Oba, there were only 13 compounds for the principal Obas. (These are now reduced to a single one, with altars to the three last Obas and a general one for all others). The decline of the Benin Kingdom and its traditions throughout the 19th century could not be more strikingly illustrated.

Provenienz

Christie’s London, 13 July 1977, lot 176

John Hewett, London

Literaturhinweise

Ben-Amos, P., The Art of Benin, London, 1980, p.38, fig.38.

William B. Fagg: ‘One Hundred Notes on Nigerian Art from Christie’s Catalogues 1974-1990’, Quaderni Poro, no.7, Milan, 1991, pl.1.

Szalay, M., Die Kunst Schwarzafrikas. Kunst und Gesellschaft. Werke aus der Sammlung des Völkerkundemuseums der Universität Zürich, Munich, 1994, no.69, fig.3.

Plankensteiner, B. (Ed.), Benin Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria, Vienna, 2007, p.157, fig.8.